This pub is situated at the north end of High Street, on the corner of Duck Street. The building had been known for many years as the Railway Inn (or Hotel). The ‘Railway’ was so named after Rushden Station opened, just off High Street, in 1894. Built by the Midland Railway Company, the station closed to passengers in 1959. It is now owned by the Rushden Historical Transport Society and is part museum and part real-ale bar.

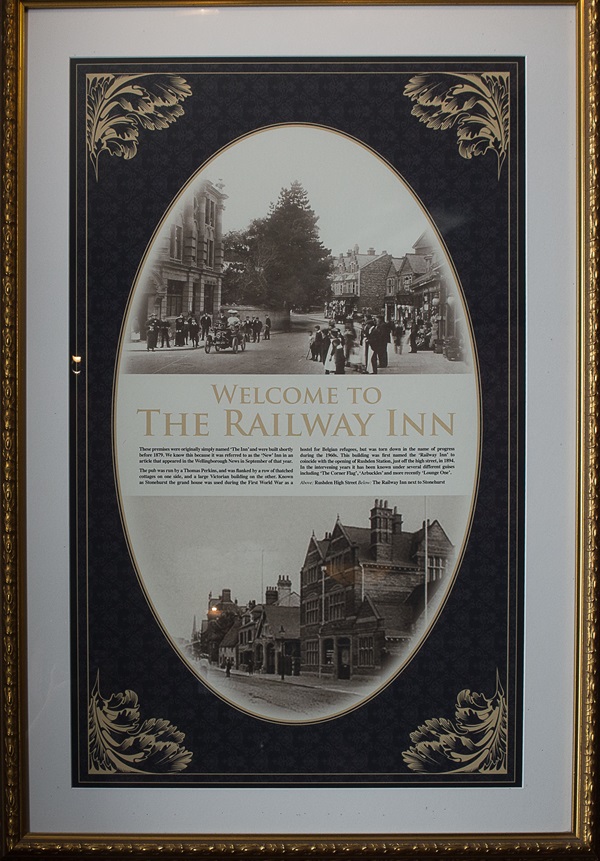

A photograph and text about The Railway Inn.

The text reads: These premises were originally simply named The Inn and were built shortly before 1879. We know this because it was referred to as the ‘New’ Inn in an article that appeared in the Wellingborough News in September of that year.

The pub was run by a Thomas Perkins, and was flanked by a row of thatched cottages on one side, and a large Victorian building on the other. Known as Stonehurst the grand house was used during the First World War as a hostel for Belgian refugees, but was torn down in the name of progress during the 1960s. This building was first named The Railway Inn to coincide with the opening of Rushden Station, just off the high street, in 1894. In the interviewing years it has been known under several different guises including The Corner Flag, Arbuckles and more recently Lounge One.

Above: Rushden High Street

Below: The Railway Inn next to Stonehurst.

Photographs and text about Lilford House.

The text reads: Lilford Hall is a stately home of 100 rooms situated in the east of Northamptonshire, south of Oundle and north of Thrapston. It was built in a Jacobean style, with a Georgian interior, around 1635. Alterations were made in the eighteenth century by Henry Flitcroft. The hall remained the home of the Lilford family until the mid 1940s when it was sold to pay the death duties of the fifth Lord Lilford.

During the late nineteenth century the grounds of the hall housed an extensive collection of birds, maintained by the fourth Baron Lilford, Thomas Littleton Powys, founder of the British Ornithologist Union. His aviaries featured various exotic birds from all over the world, including kiwis, pink-hearted ducks and lammergeirs (the great bearded vultures of southern Europe).

The hall served as a nurses’ quarters during World War II, and was bought back by the seventh Lord Lilford, who opened the aviaries to the public. At this time the aviaries contained more than 350 birds of about 110 different species. In 1990 Lilford Park was closed. Today the hall is owned by the Micklewright family.

Pictured: Lilford House and Thomas Powys, 4th Baron Lilford, in the Library at Lilford Hall

Image below: Sir Thomas Powys’ coat of arms over front porch.

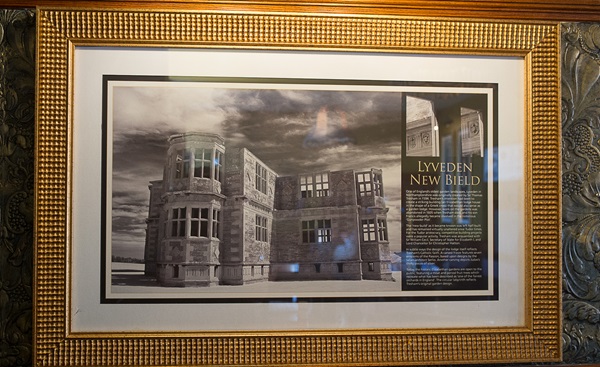

A photograph and text about Lyveden New Bield.

The text reads: One of England’s oldest garden landscapes, Lyveden in Northamptonshire was originally created by Sir Thomas Tresham in 1594. Tresham’s intention had been to create a striking building (an Elizabethan lodge house in the shape of a Greek cross) that would also serve as a garden lodge. However, work on the gardens was abandoned in 1605 when Tresham died, and his son Francis allegedly became involved in the notorious Gunpowder Plot.

The new build as it became known was left half-built and has remained virtually unaltered since Tudor times. For the Tudor aristocracy, competitive building projects were a popular activity. Tresham was acquainted with Sir William Cecil, Secretary of State for Elizabeth I, and Lord Chancellor Sir Christopher Hatton.

In subtle ways the design of the lodge itself reflects Tresham’s Catholic faith. A carved frieze features seven emblems of the Passion, based upon designs by the Italian architect Serlio. Another carving depicts Judas’s thirty pieces of silver.

Today the historic Elizabethan gardens are open to the public, featuring a moat and period fruit trees which recreate what has been described as ‘one of the fairest orchards in England’. The circular labyrinth reflects Tresham’s original garden design.

A print and text about Kimbolton Castle and the ghost of Catherine of Aragon.

The text reads: Catherine of Aragon was sent to Kimbolton Castle in nearby Kimbolton in April 1534 for refusing to dissolve her marriage to Henry VIII. She was effectively imprisoned there, and died just two years later through ill health, in January 1536. It is reputed that her ghost now wonders the castle at the height of the original flooring. As the levels have since been altered, her ghostly head and upper torso appear to glide along the upper floor while her legs and lower body are seen projecting from the ceiling below.

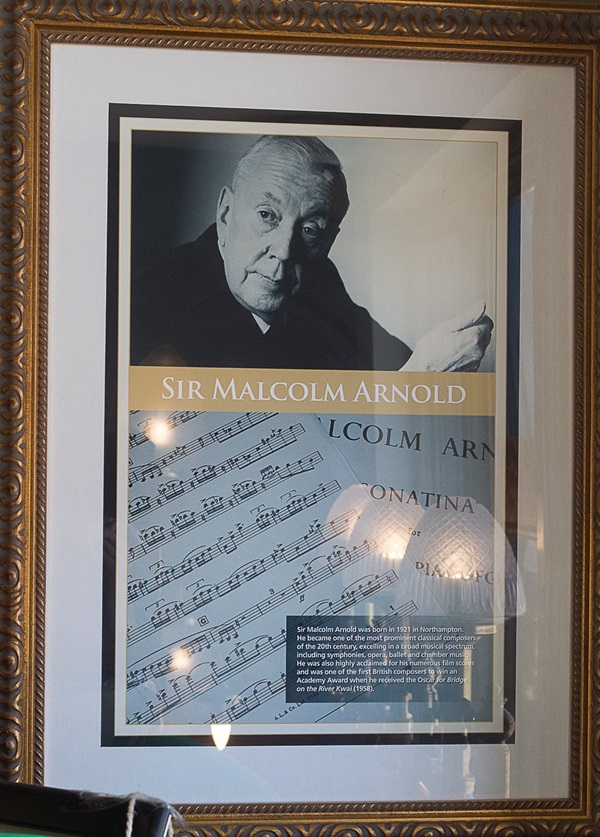

A photograph and text about Sir Malcolm Arnold.

The text reads: Sir Malcolm Arnold was born in 1921 in Northampton. He became one of the most prominent classical composers of the 20th century, excelling in a broad musical spectrum, including symphonies, opera, ballet and chamber music. He was also highly acclaimed for his numerous film scores and was one of the first British composers to win an Academy Award when he received the Oscar for Bridge on the River Kwai (1958).

A print and text about lace making in Rushden.

The text reads: The tradition of lace making in Rushden and Northamptonshire dates back to the late 1500s, and by the end of the eighteenth century Wellingborough, Northampton and the surrounding villages were the heart of the country’s lace industry.

There were village lace schools in the area teaching lacemaking to girls from the age of three. Once they had mastered the craft, they would work from home in what was truly a cottage industry. Often for twelve hours a day the young ladies would meticulously craft intricate patterns to form the trimming for babies’ bonnets and other such purposes.

There was a boom in production in the early 1870s, due in part to the Franco-Prussian war which prevented imports of French lace. The scarcity in the marketplace caused the costs of English lace to soar, as well as the wages that could be earned.

However, by the late 1880s lace making was in decline due to changing fashions and the impact of machine-made lace. Factories were able to replicate the finest handiwork for a fraction of the cost. This enabled almost all to afford what was once an expensive luxury.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk