‘Moon’ appears in the name of several Wetherspoon pubs,

linking them with the ideal pub described by the writer George Orwell. He

called his fictional pub ‘Moon

Under Water’. This pub was originally two

shops, built in c1905 on the site of an orchard. By World War I, number 84 was

a sub post office. It was later a hardware store and expanded into number 86

which had been a grocer’s for many years..

Prints and text about the Bell Junction.

The text reads: The Bell Junction in 1872, with the toll gates controlling the Staines Road on the left, and the Bath Road on the right, and the toll-keepers house between the two.

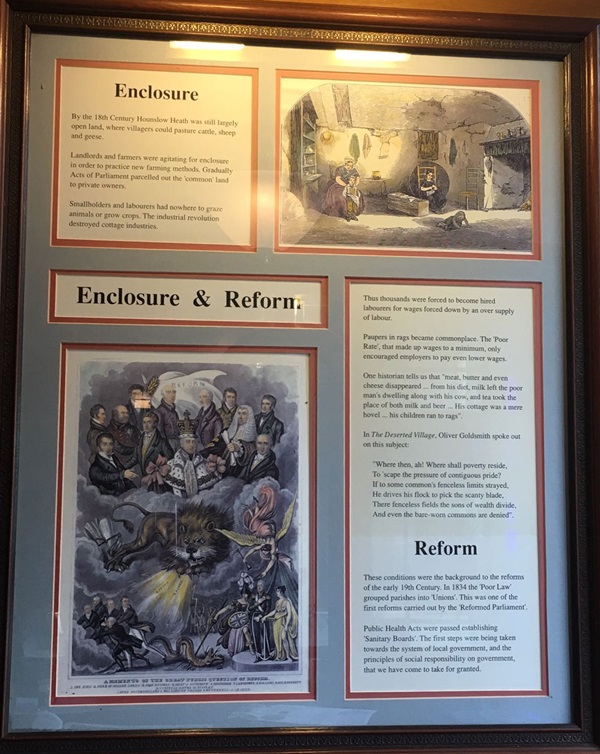

Illustrations and text about enclosure and reform.

The text reads: By the 18th century Hounslow Heath was still largely open land, where villagers could pasture cattle, sheep and geese.

Landlords and farmers were agitating for enclosure in order to practice new farming methods. Gradually Acts of Parliament parcelled out the ‘common’ land to private owners.

Smallholders and labourers had nowhere to graze animals or grow crops. The industrial revolution destroyed cottage industries.

Thus thousands were forced to become hired labourers for wages forced down by an over supply of labour.

Paupers in rags became commonplace. The ‘Poor Rate’, that made up wages to a minimum, only encouraged employers to pay even lower wages.

One historian tells us that “meat, butter and even cheese disappeared … from his diet, milk left the poor man’s dwelling along with his cow, and tea took the place of both milk and beer … His cottage was a mere hovel … his children ran to rags”.

In The Deserted Village, Oliver Goldsmith spoke out on this subject:

“Where then, ah! Where shall poverty reside,

To ‘scape the pressure of contiguous pride?

If to some common’s fenceless limits strayed,

He drives his flock to pick the scanty blade,

There fenceless fields the sons of wealth divide,

And even the bare-worn commons are denied”.

These conditions were the background to the reforms of the early 19th century. In 1834 the ‘Poor Law’ grouped parishes into ‘Unions’. This was one of the first reforms carried out by the ‘Reformed Parliament’.

Public Health Acts were passed establishing ‘Sanitary Boards’. The first steps were being taken towards the system of local government, and the principles of social responsibility on government, that we have come to take for granted.

Prints and text about the Smith brothers.

The text reads: In 1918 the Smith brothers (Ross, top and Keith above) were the first to fly from Britain to Australia. There were a number of aviation landmarks that year.

Hounslow was used as an airfield during the First World War and the first commercially operated scheduled flight left here for Paris in August 1919.

In 1920 the airport was transferred to Croydon.

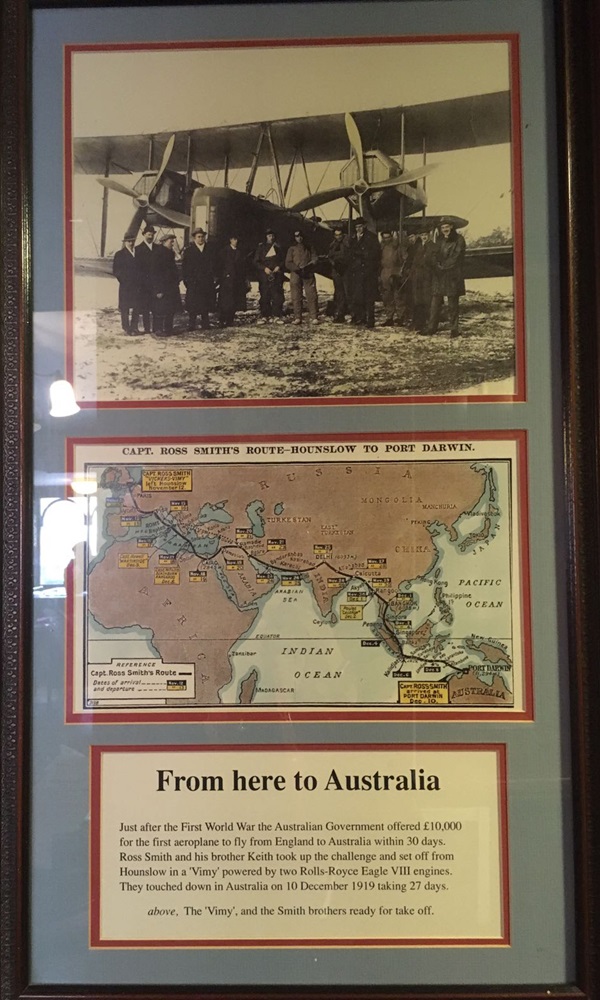

Prints and text about the first flight to Australia.

The text reads: Just after the First World War the Australian Government offered £10,000 for the first aeroplane to fly from England to Australia within 30 days. Ross Smith and his brother Keith took up the challenge and set off from Hounslow in a ‘Vimy’ powered by two Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines. They touched down in Australia on 10 December 1919 taking 27 days.

Above: The ‘Vimy’, and the Smith brothers ready for take off.

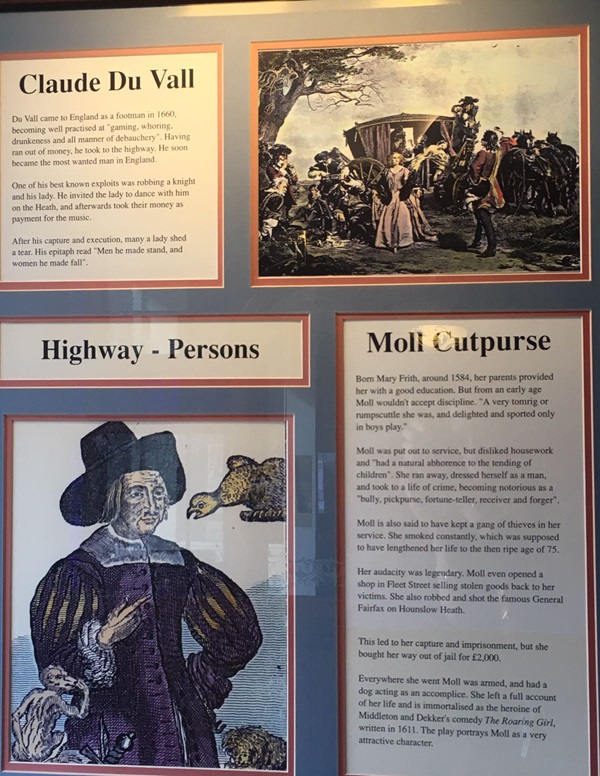

Illustrations and text about highway persons.

The text reads: Claude Du Vall

Du Vall came to England as a footman in 1660, becoming well practised at “gaming, whoring, drunkenness and all manner of debauchery”. Having ran out of money, he took to the highway. He soon became the most wanted man in England.

One of his best known exploits was robbing a knight and his lady. He invited the lady to dance with him on the Heath, and afterwards took their money as payment for the music.

After his capture and execution, many a lady shed a tear. His epitaph read “Men he made stand, and women he made fall”.

Moll Cutpurse

Born Mary Frith, around 1584, her parents provided her with a good education. But from an early age Moll wouldn’t accept discipline. “A very tomrig or rumpscuttle she was, and delighted and sported only in boys play.”

Moll was put out to service, but disliked housework and “had a natural abhorrence to the tending of children”. She ran away, dressed herself as a man, and took to a life of crime, becoming notorious as a “bully, pickpurse, fortune-teller, receiver and forger.”

Moll is also said to have kept a gang of thieves in her service. She smoked constantly, which was supposed to have lengthened her life to the then ripe age of 75.

Her audacity was legendary. Moll even opened a shop in Fleet Street selling stolen goods back to her victims. She also robbed and shot the famous General Fairfax on Hounslow Heath.

This led to her capture and imprisonment, but she bought her way out of jail for £2,000.

Everywhere she went Moll was armed, and had a dog acting as an accomplice. She left a full account of her life and is immortalised as the heroine of Middleton and Dekker’s comedy The Roaring Girl, written in 1611. The play portrays Moll as a very attractive character.

Illustrations and text about the Civil War.

The text reads: On a November morning in 1642 the inhabitants of Hounslow woke to the sound of Royalist troops marching through the town to take Brentford. Having taken Brentford their march on London was checked at Turnham Green. The next day Hounslow watched in bewilderment as the same troops marched back through in the opposite direction.

In 1647 Cromwell’s army set up camp here on the Heath. Cromwell had been informed that Parliament was conspiring against him. The following day 20,000 troops gave Hounslow another early wakening as the New Model Army marched on London to overthrow Parliament and establish Cromwell.

Following his defeat in the Civil War, King Charles I was beheaded. The Roundheads had to dispose of his body to prevent it becoming a martyr’s relic to his sympathisers.

The King’s body was sent by night, through the snow, to Windsor. The anonymous body would have passed through Hounslow.

The royal body was buried in the Chapel of St George – few people knew of the King’s last resting place.

The diarist, John Evelyn, was one of the few who did. Using one of his diary entries, a search was made in 1813.

“The coffin was found, and was in the presence of the Prince Regent…”

Apparently the body was well preserved, and the features of the severed head easily recognisable.

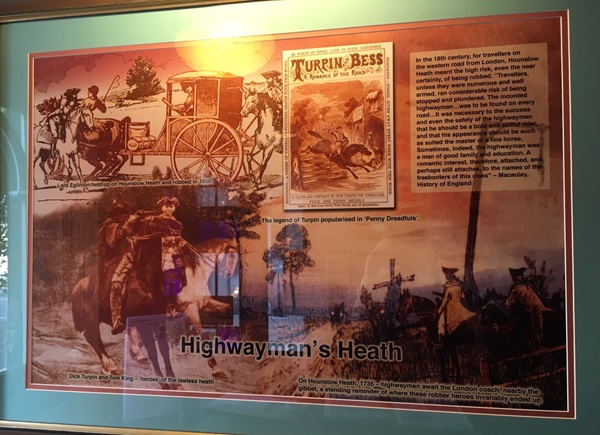

Illustrations and text about Hounslow Heath.

The text reads: In the 18th century, for travellers on the western road from London, Hounslow Heath meant the high risk, even the near certainty, of being robbed. “Travellers, unless they were numerous and well armed, ran considerable risk of being stopped and plundered. The mounted highwayman…was to be found on every road…It was necessary to the success and even the safety of the highwayman that he should be a bold and skilful rider, and that his appearance should be such as suited the master of fine a horse. Sometimes, indeed, the highwayman was a man of good family and education. A romantic interest, therefore, attached, and perhaps still attaches, to the names of the freebooters of this class” – Macaulay, History of England.

A print of High Street, Hounslow, c1920.

A print of Staines Road, Hounslow c1905.

A print of Staines Road, Hounslow, c1905.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk