This pub is the former Red Lion and Pineapple which took its name from two older pubs in the vicinity.

A print and text about transport in the area.

The text reads: 1714 was a momentous year for Acton. The Uxbridge Turnpike Road was opened with a turnpike and tollgate set up in the Vale. Immediately traffic through the village increased, bringing trade, and a bumper crop of new inns. By 1751 Acton had 21 of them.

Public transport, in the shape of the short stage coach the ‘Acton Machine’, was plying the Acton-Oxford Street route as early as 1764.

By 1856 horse-buses were being run by the London General Omnibus Company, and in 1874 the first trams appeared.

London United Tramways Ltd built the depot which became a bus garage next to this pub, when they took over the tram service in 1895. These were horse drawn trams, running on tracks, which made them more efficient than horse drawn omnibuses. But in 1901 the LUT inaugurated the electric tram service.

After World War I the trams were replaced by trolley buses, and later by the internal combustion vehicles we use today.

The Canal

The Uxbridge Turnpike Road meant local produce could be sent to London in wagons. In 1801 trade increased when the first canal was cut through North Acton. Hay from the local farms was carried by barge to the Hay Wharfs at Paddington, and refuse brought back to fertilise the fields.

The Railway

In 1837 the Great Western Railway was laid through Acton, but it didn’t stop here.

Acton’s first station came with the North and South Western Junction line in 1853. The Great Western opened a station in 1868 (now Acton Main Line).

Others followed: in 1879 the Metropolitan District Railway; in 1903 the Birmingham line of the Great Western, and in 1920 the westward extension to Ealing of the tube line.

It was the arrival of the trains that were largely responsible for the suburban development of Acton.

Usually in a deal with local house-agents the railway companies offered ‘commuted’ fare season tickets, often giving enormous reductions to tempt people who worked in London to move out of town.

Prints and text about houses in Acton.

The text reads: Friars Place was attached to St Bartholomews Priory, Smithfield, until the Dissolution of monasteries.

It has been associated with three notable names: the Earl of Essex who is said to have occupied it during the Civil War; Richard Cromwell, son of Oliver, and Izaak Walton, author of The Compleat Angler. There is no conclusive evidence that any of them lived here, but the heresay is recorded.

The “beautiful villa” was demolished in 1902 and replaced by a sausage factory (called The Friary) and later an ice cream factory. The first “stop me and try me” tricycles came from here.

Derwentwater House. About 1638 Sir Henry Garraway built a house on the east side of Horn Lane opposite The Steyne. In 1720 the widow Countess of Derwentwater, stood trial for his part in the Jacobite uprising of 1715.

The Earl pleaded guilty and threw himself on the mercy of George I, but was beheaded. The countess moved to Brussels soon after her short stay in Acton and died there in 1723.

The obelisk which the countess erected to her husband’s memory is now in Acton Park opposite Goldsmith’s almshouses. Houses and Derwentwater School now stand on the site of the old house.

Acton House stood south of Derwentwater House. In the 1650s Major-General Phillip Skippon lived there.

Bank House stood between Rectory Road and High Street. Its principal residents were Lord Francis Rous (1659-1679), speaker of the ‘Little’ Parliament in 1653; Lord Chief Justice Vaughan, and the Wegg family, who were noted in Acton for their charitable work.

Goldsmiths Almshouses. John Perryn was a goldsmith who owned 200 acres of land in Acton. When he died he left it to the Goldsmith Company.

In 1811 the Perryn Trust built the Goldsmiths Almshouses which overlook Acton Park.

Prints and text about Lady Dudley and Lola Montez.

The text reads: Lady Alice Dudley (1579-1669)

When Alice Legh (daughter of a wealthy merchant) was seventeen she married Robert Dudley, son of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, who had been the favourite of Elizabeth I.

Because of his position at Court, the Earl of Leicester had kept both his marriage and the birth of his son a secret.

Robert’s parents married again later, when it was safe, and then declared him their illegitimate son, although he was also made heir to their estate.

Robert had first married Margaret Cavendish in 1588 before his marriage to Alice. In 1605 he made an attempt to establish his legitimacy, but was unsuccessful.

Disgusted he left both the country and Alice. He went off to Florence and took service with the Medici family. With him went Elizabeth Southwell, who, he married by permission of the pope. He never returned.

Alice, then aged 25, was left with five small daughters. Dudley’s estates were seized by the crown, but she received an income.

The daughters were raised and married. An attempt to raise money on the estate by Dudley was thwarted, and Charles I made her father Thomas Legh a Baron, and created Alice a Duchess in her own right.

When Robert Dudley was finally recognised as legitimate, it was his deserted wife who took possession of the estate!

So she became a wealthy woman. She sold part of the estate (Kenilworth) to Charles II, and either sold the rest or left it as bequests to create charities.

Among her many gifts she gave a set of Communion Plates to St Mary’s Church, Acton.

Why? The clue to this is probably in a history of Middlesex published in 1706 which says she spent many of her summers in Acton, staying at the large brick house in the churchyard built by rector Kendall.

The set of plates now resides in a bank vault.

Lola Montez

In 1849 Lola Montez came to Acton as the new wife of Lieutenant Heald. She was then aged 31, whereas he had only just come of age.

Lola’s previous 12 years had been packed with incident. Marie Dolores Eliza Rosanna Gilbert - to give her real name - had run away from Scotland with her lover to avoid being married against her will.

Later she went with her first husband to India. However, they were separated due to her alleged unfaithfulness and she became a dancer, first in London and then Berlin.

In St Petersburg she was feted by the Tsar; in Paris she was due to marry the editor of La Presse but he was killed in a duel.

In 1847 she reached Munich. Here she danced, and Ludwig Carl Augustus, the King of Bavaria, fell in love with her. He presented her at Court as his ‘best friend’, created her a Baroness and also a Countess, and gave her large estates with some 2,000 serfs.

She was tempted to use her power to help people, and intrigued against Metternich. Following a revolt against the King she was driven out, and escaped disguised as a peasant girl.

Suddenly she found herself in poverty. Lola returned to England and married the young Lieutenant. She lived at Berrymead Priory. Within one month of arriving at Acton she was charged with bigamy by an aunt of her husband and the couple fled to Spain.

Lieutenant Heald died in 1856, but it seems Lola had moved on before that. She is next recorded as appearing on the stage in New York, and then married again in California.

Her colourful history was far from finished. She came back to Europe and journeyed to Australia. While she was down under she horse-whipped an editor whom she considered was impertinent in questioning her character.

Lola returned to America via France and took to public speaking.

The final chapter of her life had now begun. Unwell and without any friends, Lola was in New York, where she was sought out by a woman who had been a school-mate in their native Montrose.

This Christian lady moved her to find a deep and sincere, religious conviction.

Her life completely altered. Lola Montez devoted what turned out to be the last few months of her life to visiting poor and outcast women, to whom she left what little she then possessed.

She died on January 18 1861, aged 43 years.

A print and text about Berrymead Priory.

The text reads: Berrymead was the manor house of an estate originally in the possession of the Dean and Chapter of St Pauls Cathedral.

At the Dissolution of the monasteries Henry VIII gave the estate to Lord John Russell, 1st Earl of Bedford. His grand-daughter married into the Somerset family and Berrymead went with her.

After the Restoration the Somersets had their lands in Acton given back, but they sold Berrymead to Sir John Trevor in 1661.

He was followed by George “The Trimmer” Saville, the 1st Marquis of Halifax and later Lord Privy Seal to William and Mary.

In 1708 Evelyn Pierrepoint, Duke of Kingston-upon-Hull bought Berrymead, and his eldest daughter eloped from here to become Lady Mary Wortley Montague.

It was Lady Mary who introduced inoculation for smallpox into this country when she returned from Constantinople where her husband was ambassador.

The younger sister married the Earl of Mar, who led the 1715 Jacobite Rebellion, and had to flee for his life after its failure.

In 1802 the house was re-modelled in the new ‘Gothik’ revival manner, and it was in this romantic period that Berrymead gained the appendage ‘Priory’.

In the 1830s Lord Edward Bulwer-Lytton, the novelist, bought the house for his wife, but ended up living here alone because divorce intervened. The nuns of the Sacred Heart resided at Berrymead before moving to Roehampton. As they went out Lola Montez “dancer and adventuress” came in.

Lola was the wife of Lt. George Heald. She had been intimate with Louis I, King of Bavaria - in fact her intimacy with the King was said to have precipitated the Bavarian Uprising of 1848. Only a month after marrying her lieutenant she was accused of bigamy and the couple had to flee the country.

The house still remains. In 1855 it was bought for A Constitutional Club while the land around was sold and built upon. In time it became the administrative block for the adjacent bakery.

When the bakery was pulled down the remains of the house became the property of the local council.

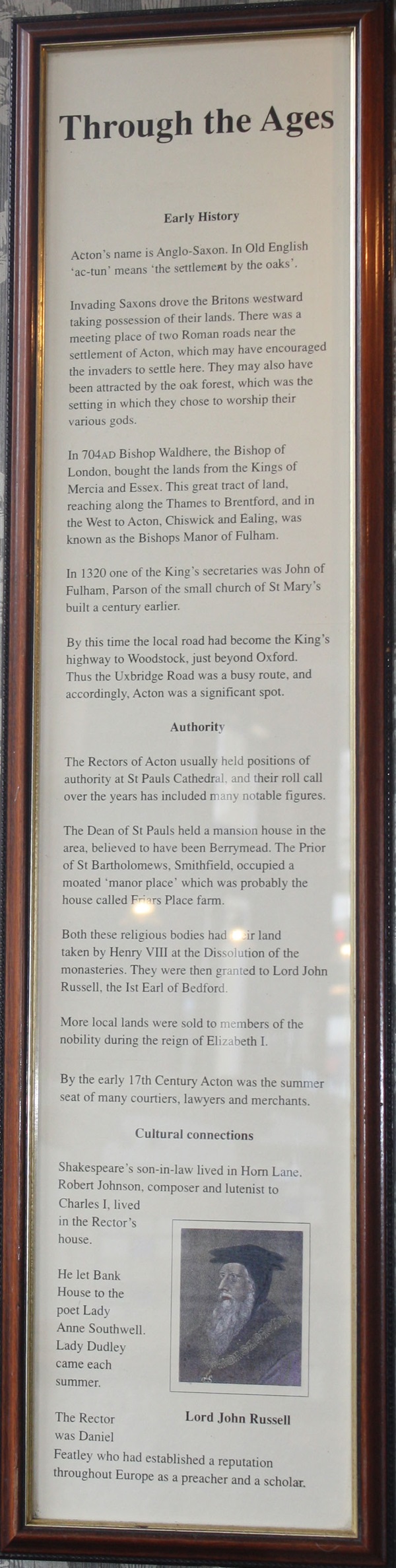

A print and text about Acton through the ages.

The text reads: Acton’s name is Anglo-Saxon. In Old English ‘ac-tun’ means ‘the settlement by the oaks’.

Invading Saxons drove the Britons westward taking possession of their lands. There was a meeting place of two Roman roads near the settlement of Acton, which may have encouraged the invaders to settle here. They may also have been attracted by the oak forest, which was the setting in which they chose to worship their various gods.

In 704AD Bishop Waldhere, the Bishop of London, bought the lands from the Kings of Mercia and Essex. This great tract of land, reaching along the Thames to Brentford, and in the West to Acton, Chiswick and Ealing, was known as the Bishops Manor of Fulham.

In 1320 one of the King’s secretaries was John of Fulham, Parson of the small church of St Mary’s built a century earlier.

By this time the local road had become the King’s highway to Woodstock, just beyond Oxford. Thus the Uxbridge route, and accordingly, Acton was a significant spot.

The Rectors of Acton usually held positions of authority at St Pauls Cathedral, and their roll call over the years has included many notable figures.

The Dean of St Pauls held a mansion house in the area, believed to have been Berrymead. The Prior of St Bartholomews, Smithfield, occupied a moated ‘manor place’ which was probably the house called Friars Place farm.

Both these religious bodies had their land taken by Henry VIII at the Dissolution of the monasteries. They were then granted to Lord John Russell, the 1st Earl of Bedford.

More local lands were sold to members of the nobility during the reign of Elizabeth I.

By the early 17th century Acton was the summer seat of many courtiers, lawyers and merchants.

Shakespeare’s son-in-law lived in Horn Lane. Robert Johnson, composer and lutenist to Charles I, lived in the Rector’s house.

He let Bank House to the poet Lady Anne Southwell. Lady Dudley came each summer.

The Rector was Daniel Featley who had established a reputation throughout Europe as a preacher and a scholar.

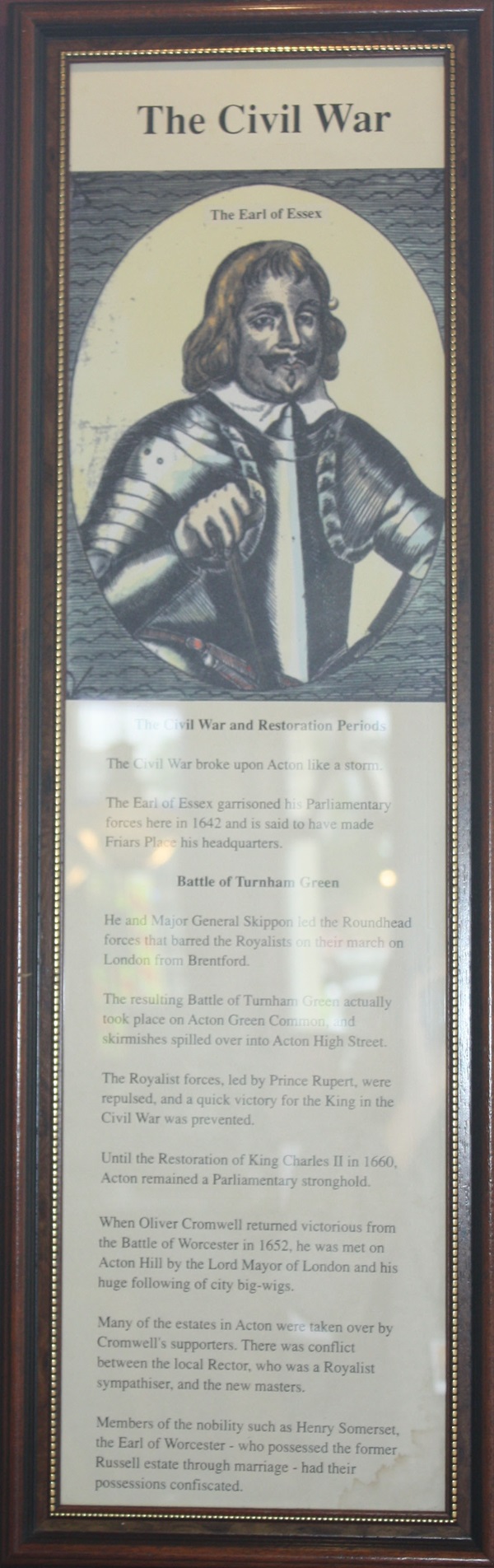

A print and text about the Civil War.

The text reads: The Civil War broke upon Acton like a storm.

The Earl of Essex garrisoned his Parliamentary forces here in 1642 and is said to have made Friars Place his headquarters.

He and Major General Skippon led the Roundhead forces that barred the Royalists on their march on London from Brentford.

The resulting Battle of Turnham Green actually took place on Acton Green Common, and skirmishes spilled over into Acton High Street.

The Royalist forces, led by Prince Rupert, were repulsed, and a quick victory for the King in the Civil War was prevented.

Until the Restoration of King Charles II in 1660, Acton remained a Parliamentary stronghold.

When Oliver Cromwell returned victorious from the Battle of Worcester in 1652, he was met on Acton Hill by the Lord Mayor of London and his huge following of city big-wigs.

Many of the estates in Acton were taken over by Cromwell’s supporters. There was conflict between the local Rector, who was a Royalist sympathiser, and the new masters.

Members of the nobility such as Henry Somerset, the Earl of Worcester- who possessed the former Russell estate through marriage- had their possessions confiscated.

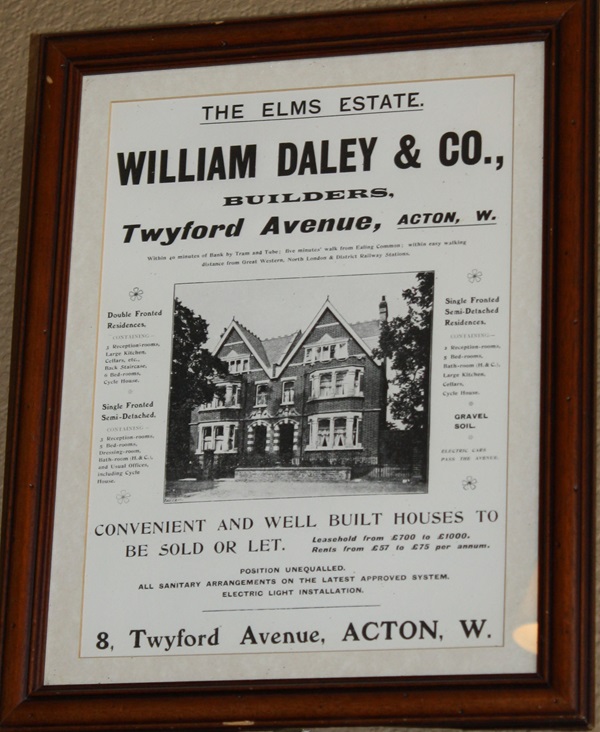

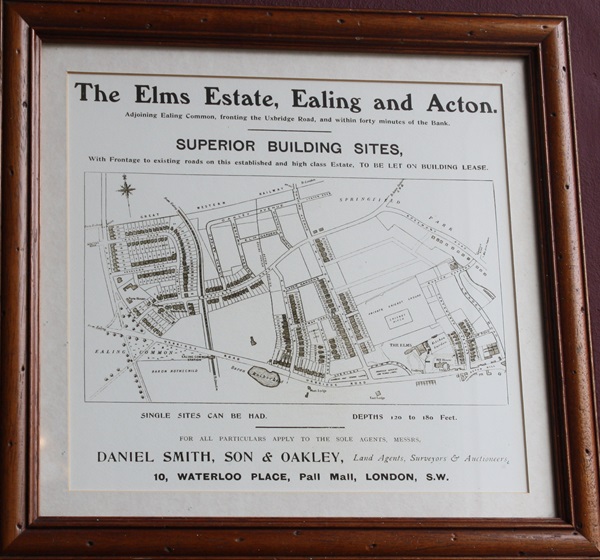

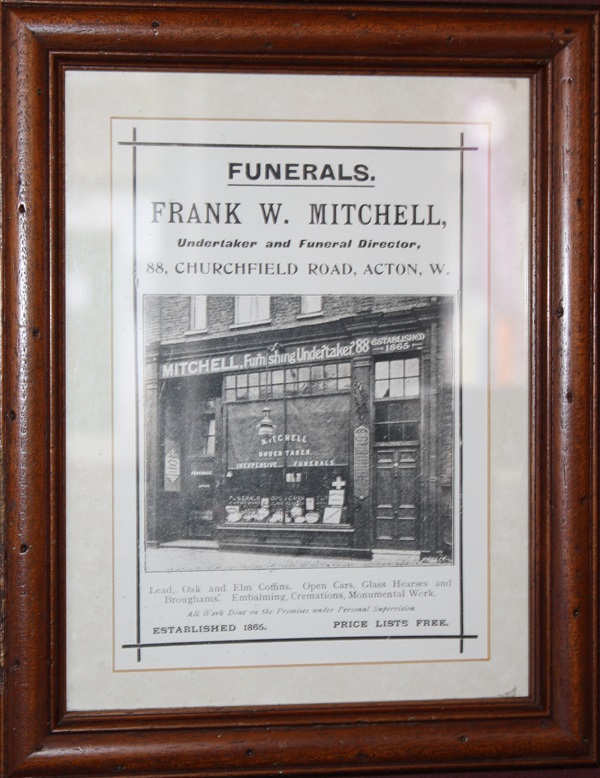

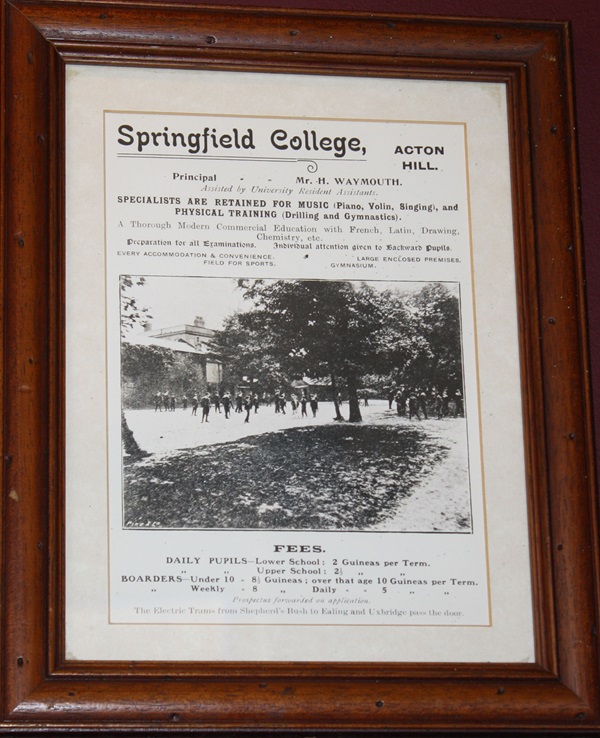

Multiple copies of old adverts and posters. These include promoting services in the local area.

Photographs and text about East Acton, c1906.

A photograph of High Street, Acton, c1910.

Photographs of Acton, c1905.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk