Nottingham born Joseph Else was Principal of the city’s School of Art during 1923–39. As well as the famous lions guarding the entrance to the Council House (in front of the pub), he was also responsible for the frieze representing the old industries of Nottingham. Else also sculpted the figures in the triangular pediment and the four groups around the base of the dome.

Photographs and text about Joseph Else.

The text reads: Almost within touching distance of the Wetherspoon freehouse, the two stone lions guarding the entrance to the Council House have been a popular meeting place since the city’s best known civic building was completed in 1929.

The lions were sculpted by Joseph Else, Principal of the Nottingham School of Art, 1929-1939. Else was also responsible for the figures in the triangular pediment above the entrance and the four groups of figures around the base of the dome.

He was helped with his prestigious commission by three of his former students. Like their former principal, Charles Dorman, James Woodford and Ernest Webb were all born in Nottingham.

Photographs and text about Joseph Else.

The text reads: Joseph Else was by far the most high profile principal of the Art School. Born in Nottingham in 1874, he worked as a lace designer’s assistant by day, and studied art and architecture in the evenings. In 1900 he won a scholarship to the Royal College of Art, and after some minor appointments became second master at Nottingham, soon becoming its principal.

Else promoted art as essential to the design of everything in the environment, from major buildings to everyday objects. His ideas were epitomized in his own life, where he sought to re-create the ‘ancient bond’ between sculpture and architecture, developing a civic style that became widely known as the ‘Nottingham mode’.

Else was an enemy of abstract and expressionist art, and tried to stem the tide of what he called ‘inartistic abnormalities’. The ‘modern movement’ he belonged to and believed in was the English one that looked back to William Morris, not the international one led by iconoclastic mavericks like Picasso.

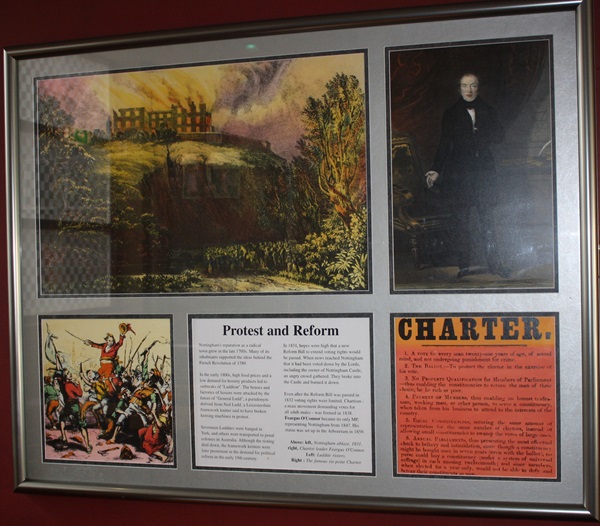

Prints and text about protest and reform in Nottingham.

The text reads: Nottingham’s reputation as a radical town grew in the late 1700s. Many of its inhabitants supported the ideas behind the French Revolution of 1789.

In the early 1800s, high food prices and a low demand for hosiery products led to outbreaks of ‘Luddism’. The houses and factories were attacked by the forces of ‘General Ludd’, a pseudonym derived from Nedd Ludd, a Leicestershire framework knitter said to have broken knitting machines in protest.

Seventeen Luddites were hanged in York, and others were transported to penal colonies in Australia. Although the rioting died down, the framework knitters were later prominent in the demand for political reform in the early 19th century.

In 1831, hopes were high that a new Reform Bill to extend voting rights would be passed. When news reached Nottingham that it had been voted down by the Lords, including the owner of Nottingham Castle, an angry crowd gathered.

They broke into the Castle and burned it down.

Even after the Reform Bill was passed in 1832 voting rights were limited. Chartism- a mass movement demanding votes for all males- was formed in 1838. Feargus O’Connor became its only MP, representing Nottingham from 1847. His statue was set up in the Arboretum in 1859.

Above: left, Nottingham ablaze, 1831, right, Chartist leader Feargus O’Connor

Left: Luddite rioters

Right: The famous six-point Charter.

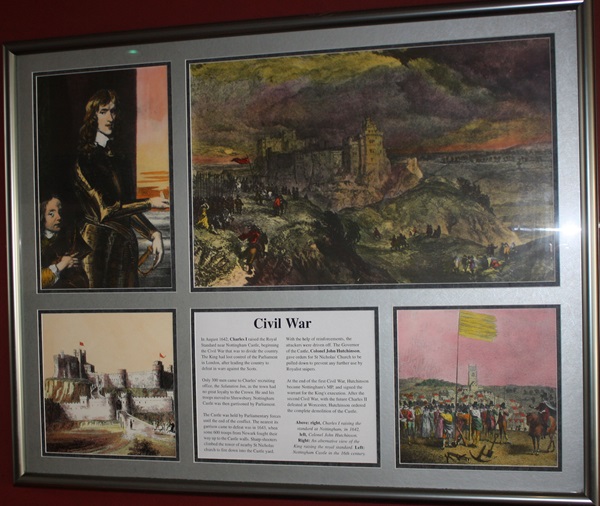

Prints and text about the Civil War.

The text reads: In August 1642, Charles I raised the Royal Standard near Nottingham Castle, beginning the Civil War that was to divide the country. The King had lost control of the Parliament in London, after leading the country to defeat in wars against the Scots.

Only 300 men came to Charles’ recruiting office, The Salutation Inn, as the town had no great loyalty to the crown. He and his troops moved to Shrewsbury. Nottingham Castle was then garrisoned by Parliament.

The castle was held by Parliamentary forces until the end of the conflict. The nearest its garrison came to defeat was in 1643, when some 600 troops from Newark fought their way up to the castle walls. Sharp-shooters climbed the tower of nearby St Nicholas church to fire down into the castle yard.

With the help of reinforcements, the attackers were driven off. The governor of the Castle, Colonel John Hutchinson, gave orders for St Nicholas’ church to be pulled down to prevent any further use by Royalist snipers.

At the end of the first Civil War, Hutchinson became Nottingham’s MP, and signed the warrant for the King’s execution. After the second Civil War, with the future Charles II defeated at Worcester, Hutchinson ordered the complete demolition of the Castle.

Above: right, Charles I raising the standard at Nottingham, in 1642, left, Colonel John Hutchinson

Right: An alternative view of the King raising the royal standard

Left: Nottingham Castle in the 16th century.

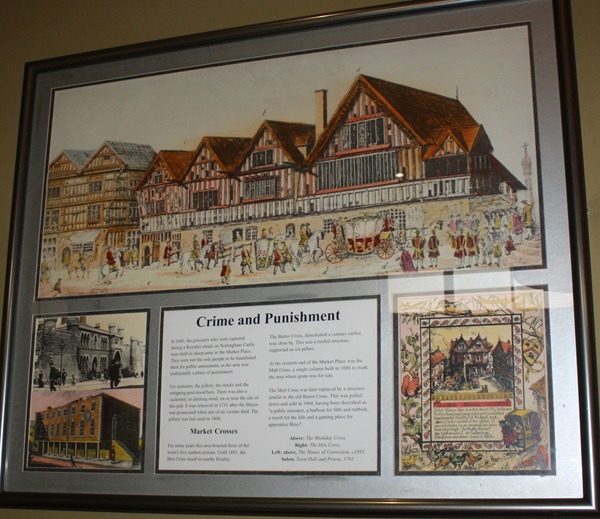

Prints and text about crime and punishment.

The text reads: In 1643, the prisoners who were captured during a Royalist attack on Nottingham Castle were held in sheep-pens in the Market Place. They were not the only people to be humiliated there for public amusement, as the area was traditionally a place of punishment.

For centuries, the pillory, the stocks and the whipping-post stood here. There was also a cuckstoll, or ducking-stool, on or near the site of this pub. It was removed in 1731 after the Mayor was prosecuted when one of its victims died. The pillory was last used in 1808.

For some years this area boasted three of the town’s five market crosses. Until 1801, the Hen Cross stood in nearby Poultry.

The Butter Cross, demolished a century earlier, was close by. This was a roofed structure, supported on six pillars.

At the western end of the Market Place was the Malt Cross, a single column built in 1686 to mark the area where grain was for sale.

The Malt Cross was later replaced by a structure similar to the old Butter Cross. This was pulled down and sold in 1804, having been described as “a public nuisance, a harbour for filth and rubbish, a resort for the Idle and a gaming place for apprentice Boys”.

Above: The Weekday Cross

Right: The Hen Cross

Left, above: The House of Correction, c.1895

Below: Town Hall and Prison, 1791.

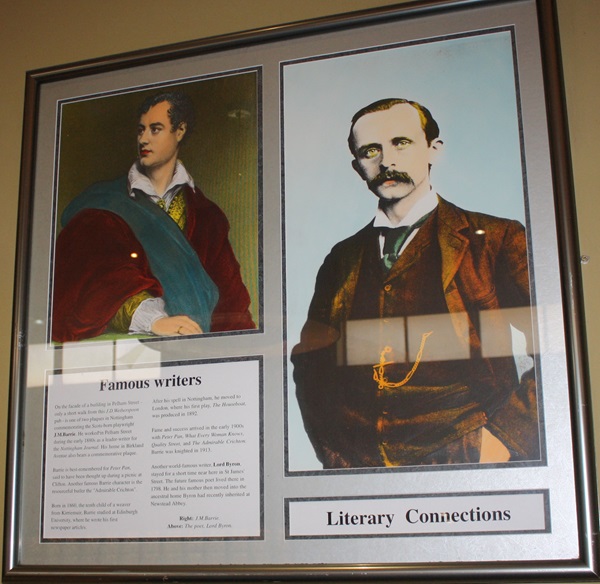

Prints and text about famous writers from Nottingham.

The text reads: On the façade of a building in Pelham Street- only a short walk from this J.D. Wetherspoon pub- is one of two plaques in Nottingham commemorating the Scots-born playwright J.M. Barrie. He worked in Pelham Street during the early 1880s as a lead writer for the Nottingham Journal. His home in Birkland Avenue also bears a commemorative plaque.

Barrie is best remembered for Peter Pan, said to have been thought up during a picnic at Clifton. Another famous Barrie character is the resourceful butler the ‘Admirable Crichton’.

Born in 1860, the tenth child of a weaver from Kirriemuir, Barrie studied at Edinburgh University, where he wrote his first newspaper articles.

After his spell in Nottingham, he moved to London, where his first play, The Houseboat, was produced in 1892.

Fame and success arrived in the early 1900s with Peter Pan, What Every Woman Knows, Quality Street, and The Admirable Crichton. Barrie was knighted in 1913.

Another world-famous writer, Lord Byron, stayed for a short time near here in St James’ Street. The future poet lived there in 1798. He and his mother then moved into the ancestral home Byron had recently inherited at Newstead Abbey.

Right: J.M. Barrie

Above: The poet, Lord Byron.

Prints and text about Moot Hall and the Council House.

The text reads: A moot, or meeting, was an assembly which developed into an early form of local government, Nottingham’s Moot Hall stood near this Wetherspoon pub, on the corner of Friar Lane.

The Moot Hall later became The Feathers Inn. Renamed The Old Moot Hall Wine Vaults, it survived until 1900. Its mock-Tudor replacement was completely destroyed in the Nottingham Blitz of 1941.

The Guildhall, from where Nottingham’s affairs were run until 1877, stood at Weekday Cross. After that, room was made in the Exchange building. This was replaced in the late 1920s by the present Council House described in the late 1920s by the present Council House described in the Times newspaper as “probably the finest municipal building outside London”.

It was officially opened in 1929 by the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VIII. In the entrance hall is a mosaic of the city’s coat of arms, officially recognised in 1614, but perhaps three centuries older.

Above: Opening of the new Council House

Left: Two scenes in the Market Place, 1910.

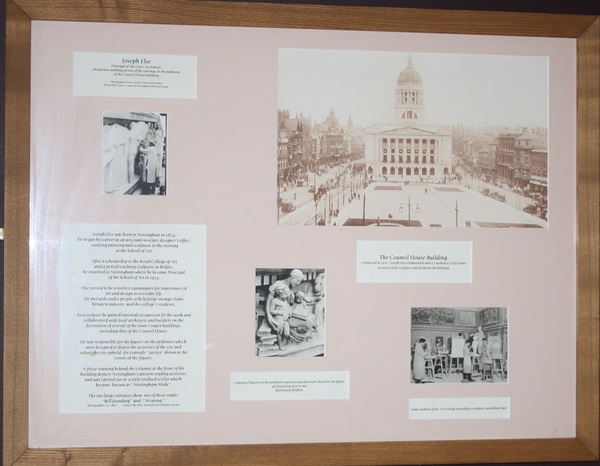

Photographs and text about Joseph Else.

The text reads: Joseph Else was born in Nottingham in 1874. He began his career as an assistant in a lace designer’s office, studying painting and sculpture in the evening at the School of Art.

After a scholarship to the Royal College of Art and a period teaching sculpture in Belfast, he returned to Nottingham where he became Principal of the School of Art in 1923.

Else proved to be a tireless campaigner for the importance of art and design in everyday life. He met with trades people to help forge stronger links between industry and the college’s students.

As a sculptor he gained national recognition for his work and collaborated with local architects and builders on the decoration of several of the town’s major buildings, including that of the Council House.

He was responsible for the figures on the pediments which were designed to depict the activities of the city and the values the city upheld- for example- “justice” shown at the centre of the figures.

A frieze running behind the columns at the front of the building depicts Nottingham’s ancient trading activities and was carried out in a style credited to Else which became known as “Nottingham Mod”.

The two large canvases show two of those trades “Bell founding” and “Weaving”.

Photographs and text about transport in Nottingham.

The text reads: The first railway reached Nottingham in 1839. The New Midland Railway Station (shown here top centre) was built in 1905.

The electric trams began running in 1901 (top right shows a corporation tram c.1917) the last ones ran in 1936.

Steam boats running on the River Trent played an important part in the growth of Nottingham as a centre of trade, (middle bottom shows steam boats on a landing stage c.1909)

A photograph of Queen Victoria’s Statue, Market Place, 1905.

A photograph of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee celebrations in Market Place, Nottingham June 1887.

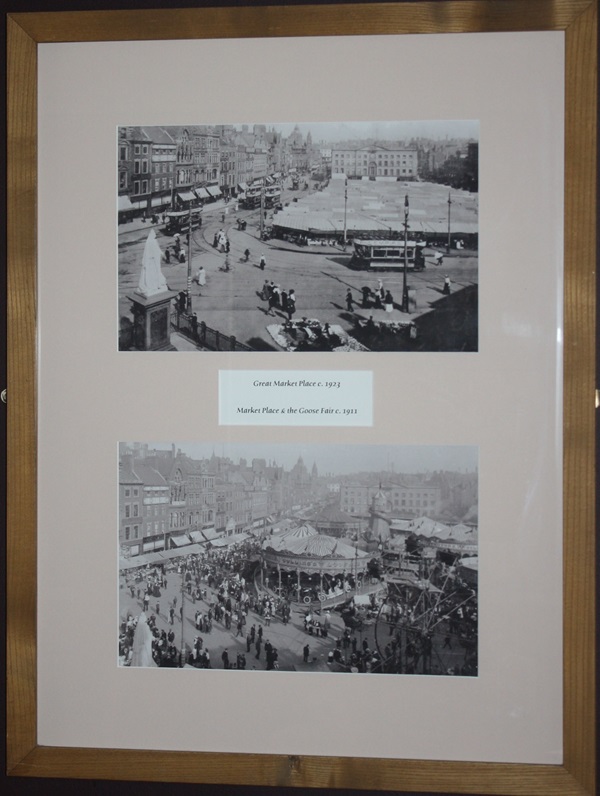

Photographs of the Great Market Place c.1923 and Market Place & the Goose Fair c.1911.

A photograph of Nottingham Market Place circa 1890.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk