Horsefair, Rugeley, Staffordshire, WS15 2EH

This pub is the former Plaza cinema, originally known as the Picture House, which first opened its doors to the public on 12 November 1934.

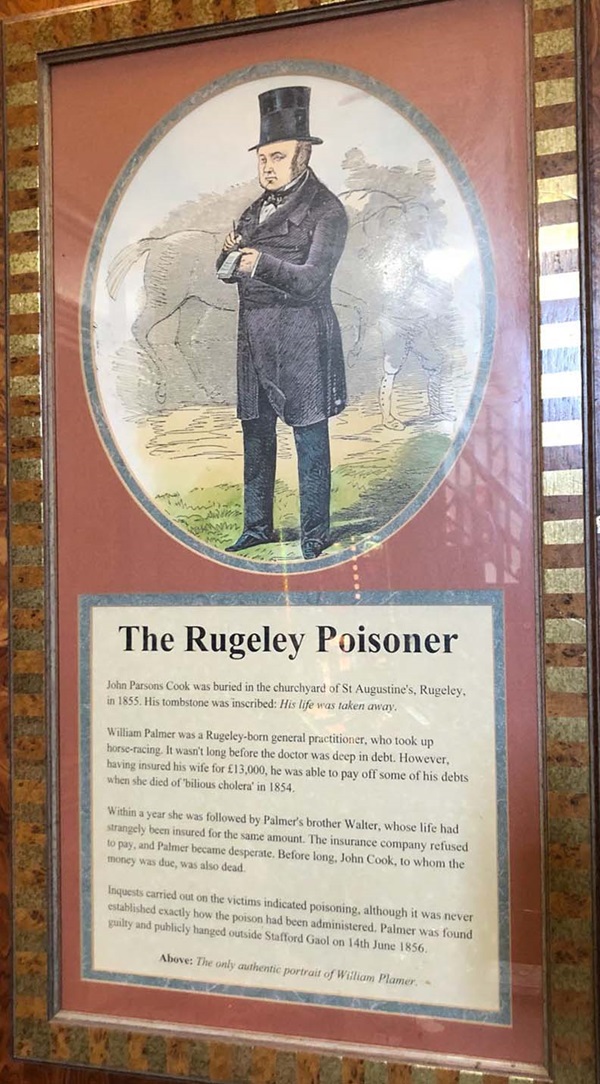

An illustration and text about the Rugeley poisoner.

The text reads: John Parsons Cook was buried in the churchyard of St Augustine’s, Rugeley, in 1855. His tombstone was inscribed: His life was taken away.

William Palmer was a Rugeley-born general practitioner, who took up horse-racing. It wasn’t long before the doctor was deep in debt. However, having insured his wife for £13,000, he was able to pay off some of his debts when she died of ‘bilious cholera’ in 1854.

Within a year she was followed by Palmer’s brother Walter, whose life had strangely been insured for the same amount. The insurance company refused to pay, and Palmer became desperate. Before long, John Cook, to whom the money was due, was also dead.

Inquests carried out on the victims indicated poisoning, although it was never established exactly how the poison had been administered. Palmer was found guilty and publicly hanged outside Staffordshire Gaol on 14 June 1856.

Above: The only authentic portrait of William Palmer.

A print and text about Lord Shaftesbury.

The text reads: Antony Ashley Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftsbury, was one of the best known philanthropists of Victorian England. For fifty years he worked, in Parliament and outside it, for the cause of the poor undefended, especially children. He visited mines and factories, asylums and hospitals, to see for himself the atrocious conditions that prevailed.

The Factory Acts of the mid 1800s improved working conditions, introduced the ten hour day, and controlled the employment of children. This was due largely to Shaftesbury’s efforts. His Coal Mines Act, and a Lunacy Act, also led to considerable changes for the better. He also has a Bill passed to protect small boys from being used as chimney sweeps.

From 1845, until his death forty years later, Shaftesbury was chairman of the Ragged Schools’ Union. He also organised training ships for homeless boys and funded emigration schemes.

Shaftesbury’s motivation was as much religious as it was humanitarian, however, the practical result of his work was the relief of suffering. When he died in 1885, thousands of London’s poorest people lined the streets in tribute.

Left: top, Ashley Cooper, the 7th Earl of Shaftesbury, below, interior of a Ragged School

Above: Lord Shaftesbury at his desk in 1884, a year before his death.

Prints and text about Angela Burdett-Coutts.

The text reads: Thomas Coutts, founder of the prestigious London bank, left around £1 million on his death in 1822. Francis Burdett, his son-in-law, was a radical MP who served several prison terms, one of them in the Tower of London, for his beliefs. His daughter Angela, born in 1814, inherited her father’s principles and her grandfather’s fortune.

Religious convictions, and the Victorian idea of self-help, directed her philanthropy. She made endowments in colonial cities to benefit British emigrants, and established a rehabilitation centre for prostitutes. She also built a housing settlement in the East End of London, and financed a training college for female teachers.

Angela Burdett-Coutts was a friend of Charles Dickens, who dedicated his novel Martin Chuzzlewil to her. In 1843, Angela asked him to inspect one of London’s first ‘Ragged Schools’ for poor children, which she had helped to fund. Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol as a result of his visit.

One of her longest-lasting gifts was a new peal of bells for St Paul’s Cathedral. In acknowledgement of her generosity, she became the first woman to be made a Freeman of the City of London.

Right: top, Angela Burdett-Coutts, below, a contraption for drying linen – designed by Angela Burdett-Coutts and Charles Dickens and sent to Florence Nightingale in the Crimea.

A print and text about William Wilberforce and the abolition of the slave trade.

The text reads: In 1781 the ‘Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade’ needed a spokesman in Parliament to make headway with its campaign. The committee eventually found its man in William Wilberforce, MP for Hull.

For twenty years, Wilberforce and a few other MPs continued the campaign in Parliament. Meanwhile, the anti-slavery campaign outside the spearheaded by men such as Thomas Clarkson. At this time, Wilberforce occasionally stayed near Rugeley, at Yoxall, where a friend was a vicar, and he worked on his anti-slavery campaigning.

Eventually, after Prime Minister William Pitt died in 1806, the Government backed Wilberforce’s Bill, which became law the following year. However, the Act only concerned trading in slaves. Existing slaves in the British Colonies were not freed until after the passing of another Act in 1833, a few months after Wilberforce had died.

Above: Thomas Clarkson

Top right: William Wilberforce.

A print and text about Robert Owen.

The text reads: Born in Wales in 1771, Robert Owen began his working life at his father’s saddlery and then in a draper’s shop. At the age of 19 he was the manager of a Manchester cotton-mill, interesting himself in questions of science and philosophy. When he moved to New Lanark, in Scotland, he set about creating a ‘model’ working environment there.

At New Lanark Owen provided the workforce with housing which had proper sanitation, reduced working hours, and refused to employ young children. Instead he provided schools with playgrounds, and the first day-nurseries. There were also company shops, where good inexpensive food was supplied in exchange for tokens. These stores were the beginning of the Co-operative movement and the forerunner of the present day Co-op trading empire.

In 1824, Owen went to America to found other self-sufficient communities. His Community of Equality at New Harmony, Indiana, failed and bankrupted him. When he returned to Britain, Owen sold his New Lanark mills. Soon afterwards, he organized the Grand National Consolidated Trade Union, which also failed. However, the best of Robert Owen’s ideas on education and co-operation have survived him.

A photograph of the Picture House, Rugeley.

A sculpture entitled Iron in the Soul.

Rugeley was prominent in the Midland’s iron industry from the Middle Ages to Elizabethan times, and again in the Industrial Revolution at the end of the 18th century.

The woods, ironstone, coal and clay in the area, together with available water power, led to the town becoming an industrial settlement. There were forges along the Rising Brook from the Middle Ages, and by 1380 there were 17 workers in iron here. In 1682 there was a forge near Slitting Mill and between 1692 and 1710 a slitting mill (for working the forged iron) at Rugeley was handling most of the output of Staffordshire’s ironworks. There was also a forge in the centre of Rugeley around 1775 and by 1834 two forges, rolling mills and two iron foundries.

The larger of the two iron foundries in Rugeley in 1834 has ‘a gas apparatus which supplies both its own workshops and the town with its brilliant vapour’. By 1851 there were a large sheet iron and tin plate mill and two foundries in the town.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.