The word ‘moon’ appears in the name of several Wetherspoon pubs. It is a link with the ideal pub described in detail by the writer George Orwell, who named his fictional pub ‘Moon Under Water’. Numbers 58–60 High Street (now The Full Moon) were extended back to King Street during the 1920/30s. Around that time, drapers moved into number 58, while the Valeting Service & Speedy Laundry Company began its long stay at number 60.

Illustrations and text about Himley Hall.

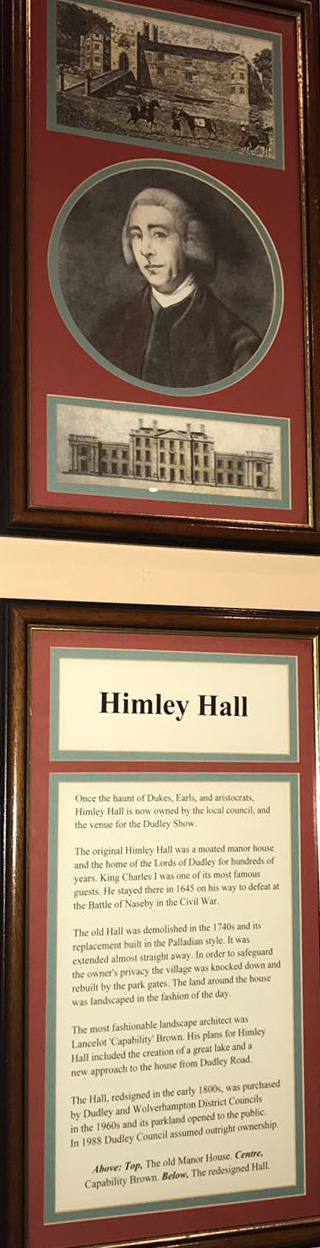

The text reads: Once the haunt of dukes, earls, and aristocrats, Himley Hall is now owned by the local council, and the venue for the Dudley Show.

The original Himley Hall was a moated manor house and the home of the Lords of Dudley for hundreds of years. King Charles I was once of it most famous guests. He stayed there in 1645 on his way to defeat at the Battle of Naseby in the Civil War.

The old hall was demolished in the 1740s and its replacement built in the Palladian style. It was extended almost straight away. In order to safeguard the owner’s privacy the village was knocked down and rebuilt by the park gates. The land around the house was landscaped in the fashion of the day.

The most fashionable landscape architect was Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown. His plans for Himley Hall included the creation of a great lake and a new approach to the house from Dudley Road.

The hall, redesigned in the early 1800s, was purchased by Dudley and Wolverhampton District Councils in the 1960s and its parkland opened to the public. In 1988 Dudley Council assumed outright ownership.

Above: top, the old Manor House

Centre: Capability Brown Below, The redesigned hall.

Illustrations and text about the Newcomen engine.

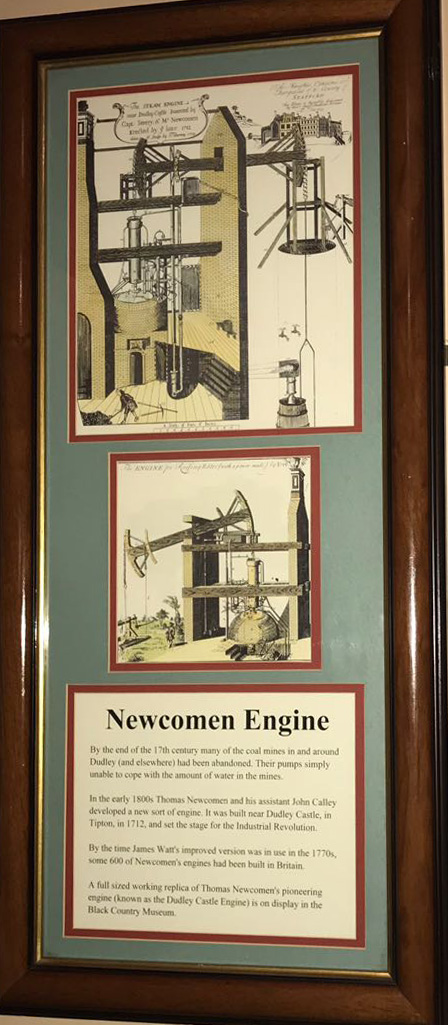

The text reads: By the end of the 17th century many of the coal mines in and around Dudley (and elsewhere) had been abandoned. Their pumps simply unable to cope with the amount of water in the mines.

In the early 1800s Thomas Newcomen and his assistant John Calley developed a new sort of engine. It was built near Dudley Castle, in Tipton, in 1712, and set the stage for the Industrial Revolution.

By the time James Watt’s improved version was in use in the 1770s, some 600 of Newcomen’s engines had been built in Britain.

A full sized working replica of Thomas Newcomen’s pioneering engine (known as the Dudley Castle Engine) is on display in the Black Country Musuem.

Illustrations and text about fossils and glass.

The text reads:

Wren’s Nest

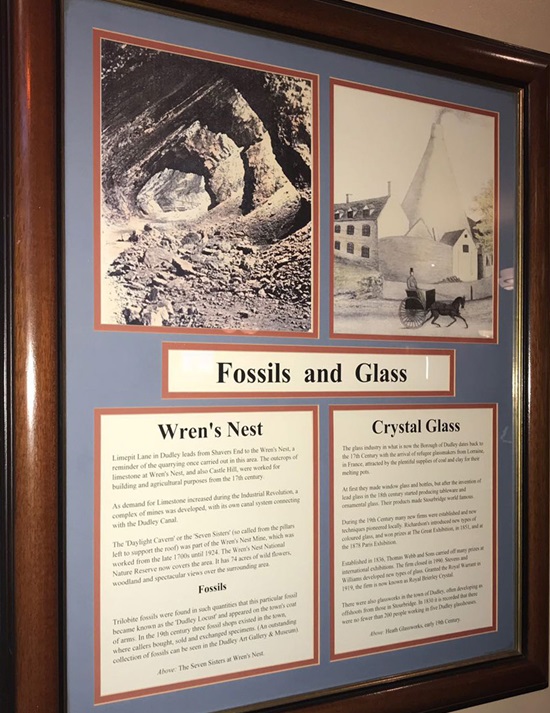

Limepit Lane in Dudley leads from Shavers End to the Wren’s Nest, a reminder of the quarrying once carried out in this area. The outcrops of limestone at Wren’s Nest, and also Castle Hill, were worked for building and agricultural purposes from the 17th century.

As demand for Limestone increased during the Industrial Revolution, a complex of mines was developed, with its own canal system connecting with the Dudley Canal.

The ‘Daylight Cavern’ or the ‘Seven Sisters’ (so called from the pillars left to support the roof) was part of the Wren’s Nest Mine, which was worked from the late 1700s until 1924. The Wren’s Nest National Nature Reserve now covers the area. It has 74 acres of wild flowers, woodland and spectacular views over the surrounding area.

Trilobite fossils were found in such quantities that this particular fossil became known as the ‘Dudley Locust’ and appeared on the town’s coat of arms. In the 19th century three fossil shops existed in the town, where callers bought, sold and exchanged specimens. (An outstanding collection of fossils can be seen in the Dudley Art Gallery and Museum).

Above: The Seven Sisters at Wren’s Nest.

Crystal Glass

The glass industry in what is now the Borough of Dudley dates back to the 17th century with the arrival of refugee glassmakers from Lorraine, in France, attracted by the plentiful supplies of coal and clay for their melting pots.

At first they made window glass and bottles, but after the invention of lead glass in the 18th century, started producing tableware and ornamental glass. Their products made Stourbridge world famous.

During the 19th century many new firms were established and new techniques pioneered locally. Richardson’s introduced new types of coloured glass, and won prizes at The Great Exhibition, in 1851, and at the 1878 Paris Exhibition.

Established in 1836, Thomas Webb and Sons carried off many prizes at international exhibitions. The firm closed in 1990. Stevens and Williams developed new types of glass. Granted the Royal Warrant in 1919, the firm is now known as Royal Brierley Crystal.

There were also glass works in the town of Dudley, often developing as offshoots from those in Stourbridge. In 1830 it is recorded that there were no fewer than 200 people working in five Dudley glasshouses.

Above: Heath Glassworks, early 19th century.

Illustrations, prints and text about the history of Dudley.

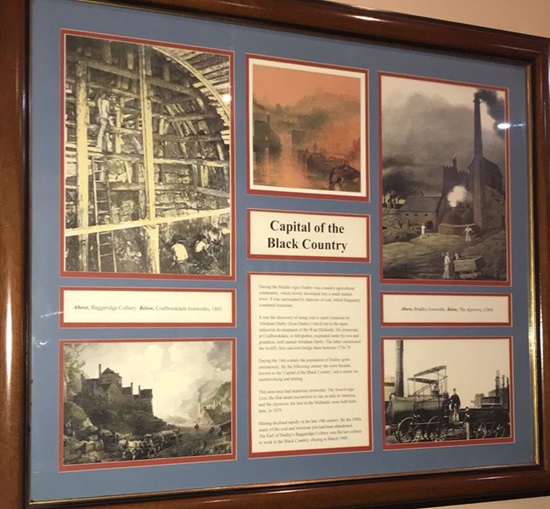

The text reads: During the Middle Ages Dudley was a mainly agricultural community, which slowly developed into a small market town. It was surrounded by deposits of coal, which frequently contained ironstone.

It was the discovery of using coal to smelt ironstone by Abraham Darby (from Dudley) which led to the rapid industrial development of the West Midlands. His ironworks at Coalbrookdale, in Shropshire, expanded under his son and grandson, both named Abraham Darby. The latter constructed the world’s first cast-iron bridge there between 1776-79.

During the 18th century the population of Dudley grew enormously. By the following century the town became known as the ‘Capital of the Black Country’, and a centre for metalworking and mining.

This area once had numerous ironworks. The Stourbridge Lion, the first steam locomotion to run on rails in America, and the Agenoria, the first in the Midlands, were both built here, in 1829.

Mining declined rapidly in the late 19th century. By the 1880s many of the coal and ironstone pits had been abandoned. The Earl of Dudley’s Baggeridge Colliery was the last colliery to work in the Black Country, closing in March 1968.

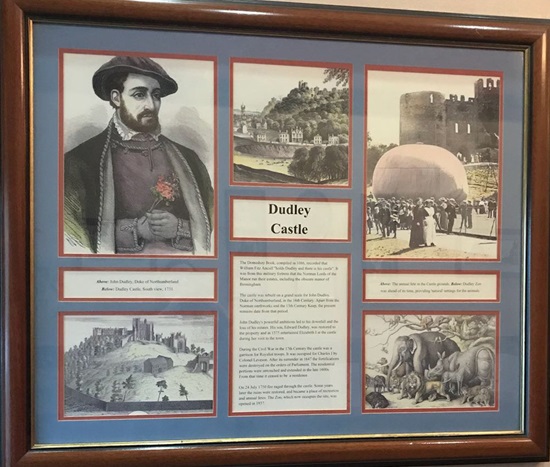

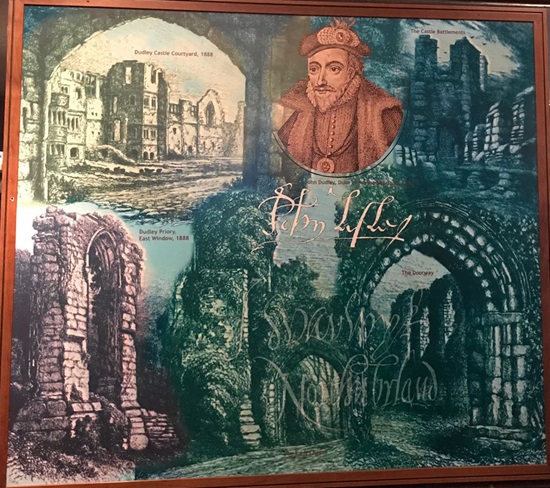

Illustrations and text about Dudley Castle.

The text reads: The Domesday Book, compiled in 1086, recorded that William Fitz Anculf “holds Dudley and there is his castle”. It was from this military fortress that the Norman Lords of the Manor ran their estates, including the obscure manor of Birmingham.

The castle was rebuilt on a grand scale for John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, in the 16th century. Apart from the Norman earthworks and the 13th century Keep, the present remains date from that period.

John Dudley’s powerful ambitions led to his downfall and the loss of his estates. His son, Edward Dudley, was restored to the property and in 1575 entertained Elizabeth I at the castle during her visit to the town.

During the Civil War in the 17th century the castle was a garrison for Royalist troops. It was occupied for Charles I by Colonel Leveson. After its surrender in 1647 the fortifications were destroyed on the orders of Parliament. The residential portions were untouched and extended in the late 1600s. From that time it ceased to be a residence.

On 24 July fire raged through the castle. Some years later the ruins were restored, and became a place of recreation and annual fetes. The zoo, which now occupies the site, was opened in 1937.

Illustrations of Dudley Castle.

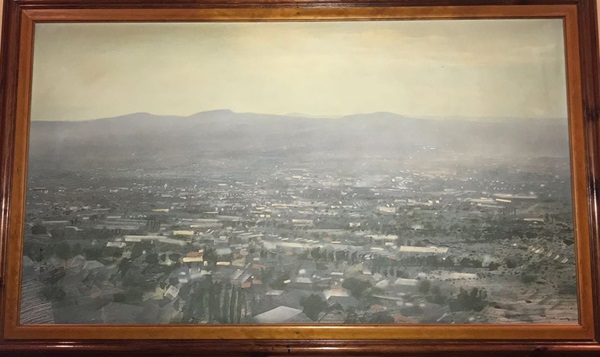

A painting entitled September Nightfall in the Black Country, by Robert Perry RBSA (Royal Birmingham Society of Artists).

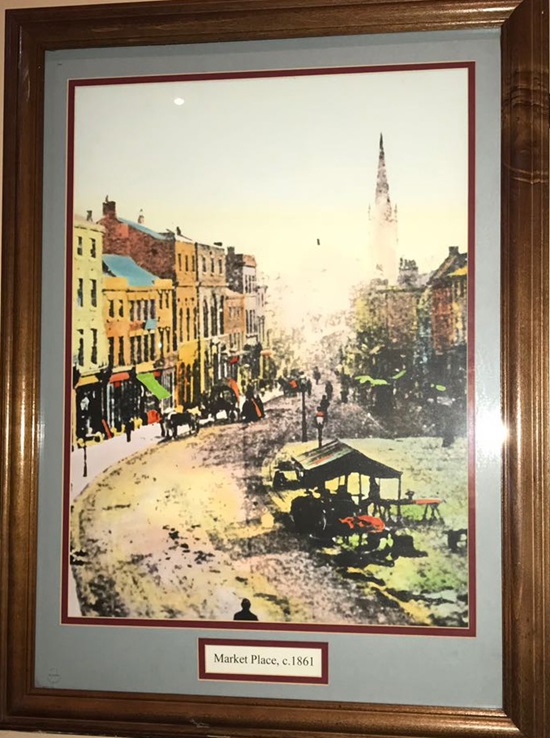

A print of Market Place, c1861.

A photograph of a Cadley tram, Dudley, c1908.

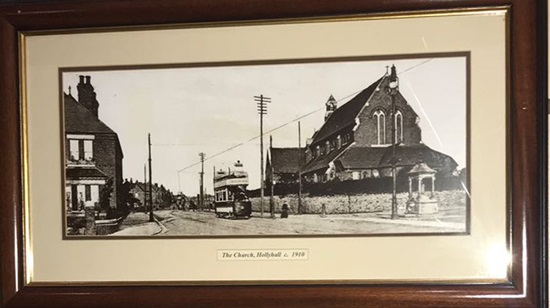

A photograph of the church, Hollyhall, c1910.

A photograph of High Street, Dudley, c1910.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk