Castleford and glass-making once went hand in hand. During the 19th century, glassworks (the industry recalled in the name of this Wetherspoon pub) sprang up all over Castleford – the first glasshouse opening in 1829. Glass production became the staple trade of the town, turning out bottles by the million, for both export and home use. At first, bottles were handmade, but, in due course, automation was introduced and, inevitably, many small firms closed. The last of Castleford’s bottle manufacturers closed its doors in the early 1980s.

Text about coal, clay and glass.

The text reads: Castleford’s industrial heyday was built on pottery, coal mining and glass. Little is now left of the town’s thriving pottery industry, except the name Pottery Street, although kilns burned with locally-produced coal throughout the 18th and 19th centuries.

Local supplies of clay also fuelled its development, while the rivers Aire and Calder proved ideal export routes. The first pottery was established in 1724 by the appropriately-named John Clay. Dunderdales produced high quality fineware that is now rare and much prized by collectors. Family-run Clokie’s finally closed in 1961.

Coal mining began as early as the 16th century, when records reveal that people burned ‘much Yearth cole, by cause it is plentiful and sold goode chepe’. The industry took off in the 19th century, when a string of collieries open. By 1899, they produced a million tons of hand hewn coal. When the pits closed in the 1980s, some 3,000 local jobs were lost.

Glass-making began in the 17th century, and 200 years later, it had become Castleford’s main industry. Bottles were made by the million for use at home and abroad. Technology transformed production in 1887, when the first semi-automatic bottle-making machine in the country was installed. The industry disappeared with the closure of United Glass in 1983.

A print and text about Castleford’s post office and sorting office.

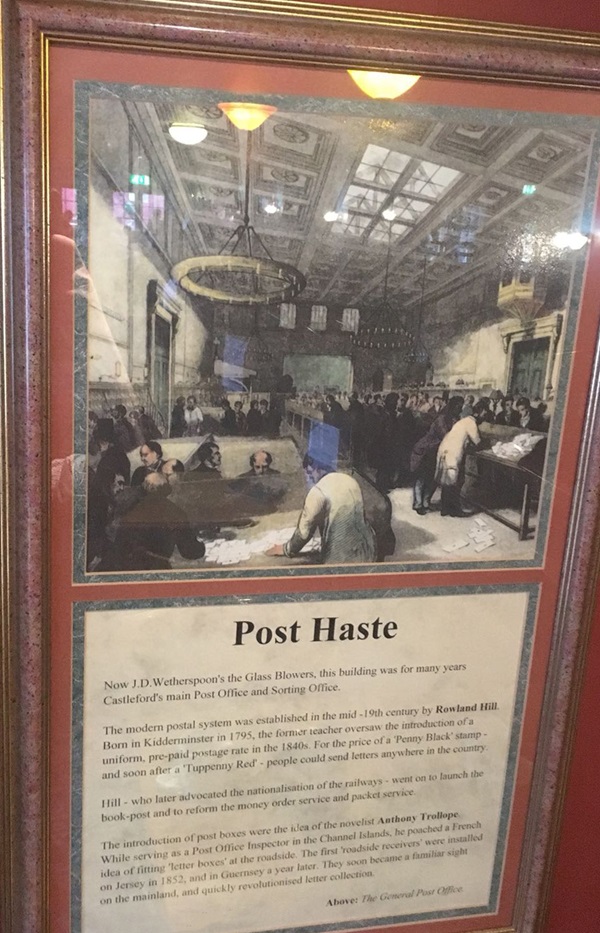

The text reads: Now J D Wetherspoon’s The Glass Blower, this building was for many years Castleford’s main post office and sorting office.

The modern postal system was established in the mid–19th century by Rowland Hill. Born in Kidderminster in 1795, the former teacher oversaw the introduction of a uniform, pre-paid postage rate in the 1840s. For the price of a ‘Penny Black’ stamp – and soon after a ‘Tuppenny Red’ – people could send letters anywhere in the country.

Hill – who later advocated the nationalisation of the railways – went on to the launch the book-post and to reform the money order service and packet service.

The introduction of post boxes were the idea of the novelist Anthony Trollope. While serving as a post office inspector in the Channel Islands, he poached a French idea of fitting letter boxes at the roadside. The first roadside receivers were installed on Jersey in 1852, and in Guernsey a year later. They soon became a familiar sight on the mainland, and quickly revolutionised letter collection.

Above: The general post office.

The old post boxes can still be found on the front of the pub today.

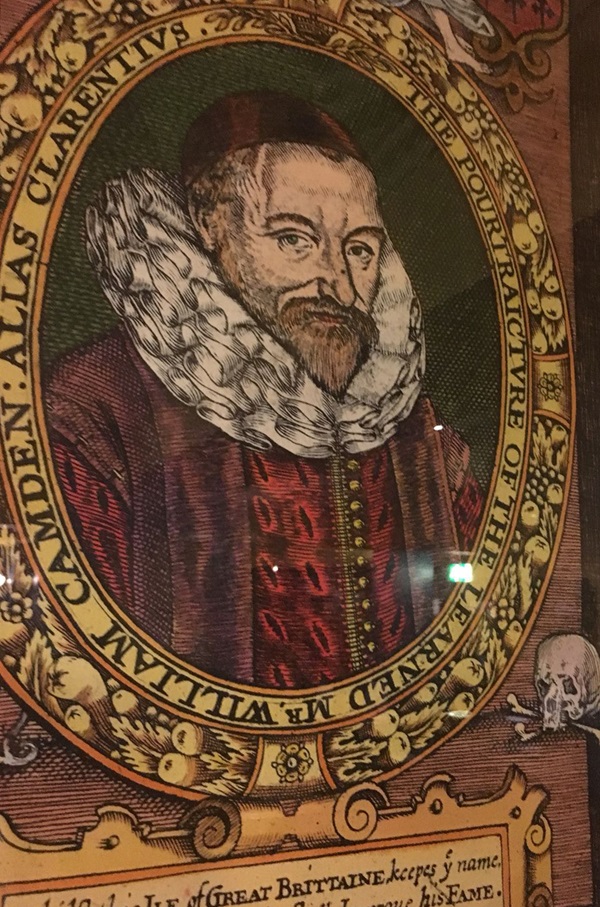

An illustration and text about William Camden.

The text reads: Over the centuries, leading antiquarians have been impressed by Castleford’s treasure trove from the past. In 1586, William Camden remarked: “The plain and remarkable remains of antiquity are confirmed by those great number of coins, called by the common people Sarasins Heads, dug up here in Beanfield, a place near the Church”.

In the early 18th century, William Stukeley observed: “A man told us he had formerly ploughed up a dozen Roman coins in a day, and urns are often found as well as stone pavements, foundations etc… the Roman Castrum was where the Church now stands, built probably out of its ruins. The low ground of the ditch that encompassed it is manifest”.

John Leland, historian to King Henry VIII, referred to ‘Castleford Bridge of seven arches’ in 1522. He also noted a pasture enclosed by a ditch and the remains of a castle.

The bridge, forerunner of Castleford’s oldest structural landmark – an elegant three-arched structure built in 1808 – also attracted the attention of Celia Fiennes, who passed through the town in 1697.

It is thought that Celia may well be the ‘fine lady on a white horse’ referred to in the popular children’s nursery rhyme Banbury Cross.

Above: William Camden.

Photographs and text about entertainment in Castleford.

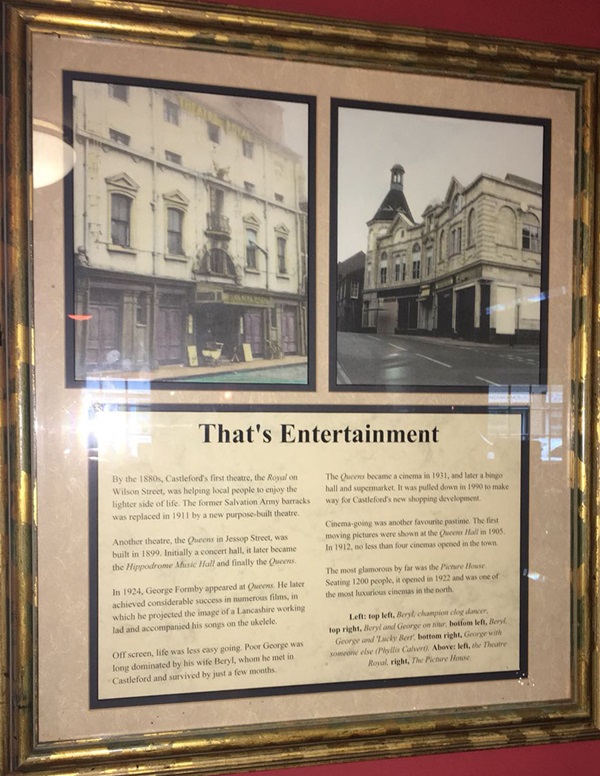

The text reads: By the 1880s, Castleford’s first theatre, the Royal on Wilson Street, was helping local people to enjoy the lighter side of life. The former Salvation Army barracks was replaced in 1911 by a new purpose-built theatre.

Another theatre, the Queens in Jessop Street, was built in 1899. Initially a concert hall, it later became the Hippodrome Music Hall and finally the Queens.

In 1924, George Formby appeared at Queens. He later achieved considerable success in numerous films, in which he projected the image of a Lancashire working lad and accompanied his songs on the ukulele.

Off screen, life was less easy going. Poor George was long dominated by his wife Beryl, whom he met in Castleford and survived by just a few months.

The Queens became a cinema in 1931, and later a bingo hall and supermarket. It was pulled down in 1990 to make way for Castleford’s new shopping development.

Cinema-going was another favourite pastime. The first moving pictures were shown at the Queens Hall in 1905. In 1912, no less than four cinemas opened in the town.

The most glamorous by far was the Picture House. Seating 1200 people, it opened in 1922 and was one of the most luxurious cinemas in the north.

Above: left, The Theatre Royal, right, The Picture House.

A print and text about George Bradley.

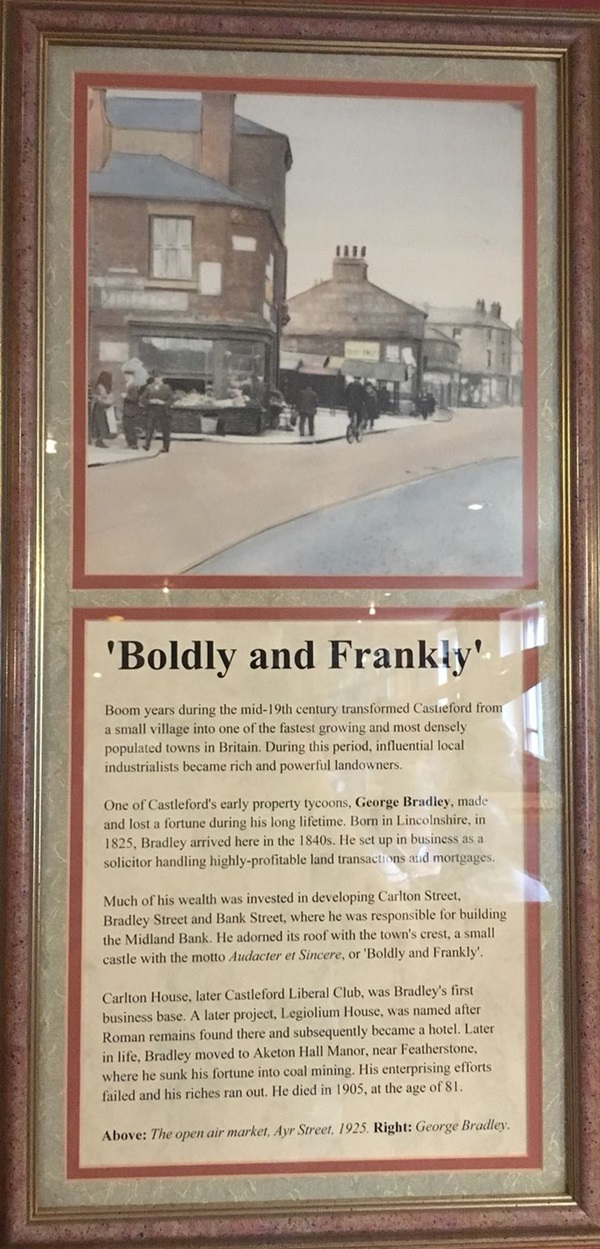

The text reads: Boom years during the mid-19th century transformed Castleford from a small village into one of the fastest growing and most densely populated towns in Britain. During this period, influential local industrialists became rich and powerful landowners.

One of Castleford’s early property tycoons, George Bradley, made and lost a fortune during his long lifetime. Born in Lincolnshire, in 1825, Bradley arrived here in the 1840s. He set up in business as a solicitor handling highly-profitable land transactions and mortgages.

Much of his wealth was invested in developing Carlton Street, Bradley Street and Bank Street, where he was responsible for building the Midland Bank. He adorned its roof with the town’s crest, a small castle with the motto Audacter et Sincere, or ‘Boldly and Frankly’.

Carlton House, later Castleford Liberal Club, was Bradley’s first business base. A later project, Legiolium House, was named after Roman remains found there and subsequently became a hotel. Later in life, Bradley moved to Aketon Hall Manor, near Featherstone, where he sunk his fortune into coal mining. His enterprising efforts failed and his riches ran out. He died in 1905, at the age of 81.

Above: The open air market, Ayr Street, 1925.

Photographs and text about Henry Moore.

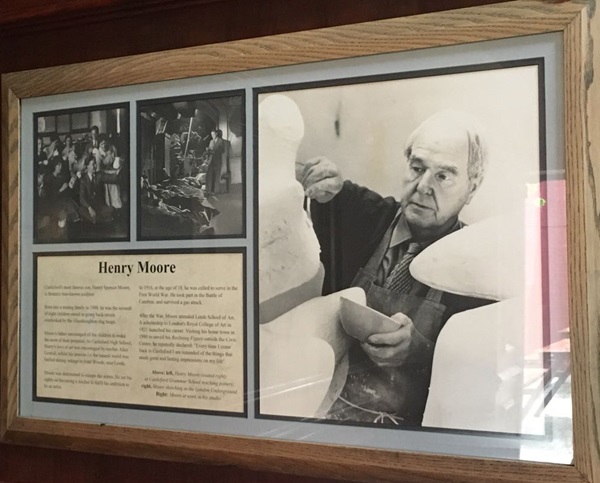

The text reads: Castleford’s most famous son, Henry Spencer Moore, is Britain’s best known-sculptor.

Born into a mining family in 1898, he was the seventh of eight children raised in grimy back streets overlooked by the Glasshoughton slag heaps.

Moore’s father encouraged all his children to make the most of their potential. At Castleford High School, Henry’s love of art was encouraged by teacher Alice Gostick, whilst his passion for the natural world was fuelled during outings to Adel Woods, near Leeds.

Moore was determined to escape the mines. He set his sights on becoming a teacher to fulfil his ambition to be an artist.

In 1916, at the age of 18, he was called to serve in the First World War. He took part in the Battle of Cambrai, and survived a gas attack.

After the war, Moore attended Leeds School of Art. A scholarship to London’s Royal College of Art in 1921 launched his career. Visiting his home town in 1980 to unveil his Reclining Figure outside the Civic Centre, he reputedly declared: “Every time I come back to Castleford I am reminded of the things that made great and lasting impressions on my life”.

Above: left, Henry Moore (seated right) at Castleford Grammar School teaching pottery, right, Moore sketching in the London Underground

Right: Moore at work in his studio.

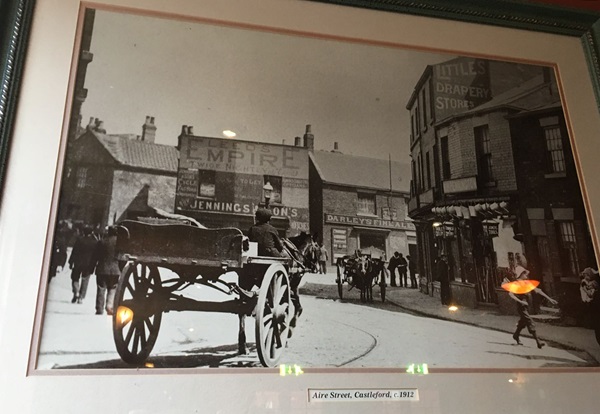

A photograph of Aire street, Castleford, c1912.

A photograph of Carlton Street, Castleford, c1910.

A photograph of Central Dock, Castleford, c1910.

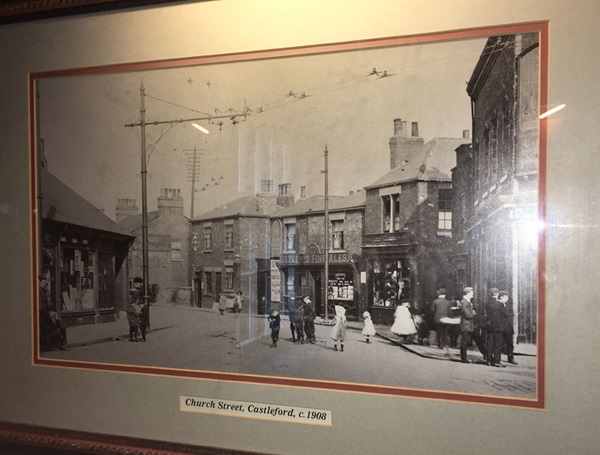

A photograph of Church Street, Castleford, c1908.

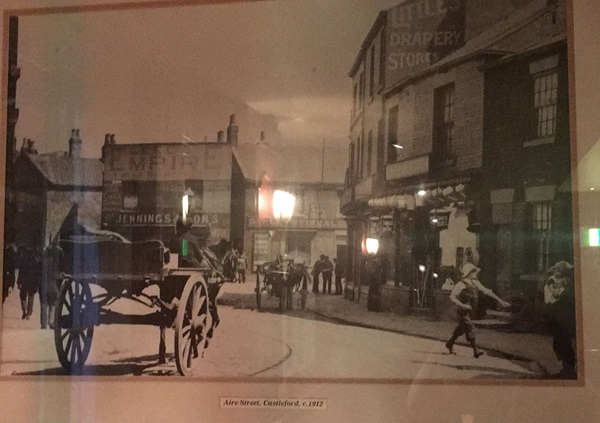

A photograph of Aire Street, Castleford, c1912.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk