This pub takes its name from the malt whisky which made Wishaw famous. Around this time, cotton-weaving was established in Wishaw. Domestic hand loom weaving and finishing became the main livelihood for many families and remained so well into the 19th century.

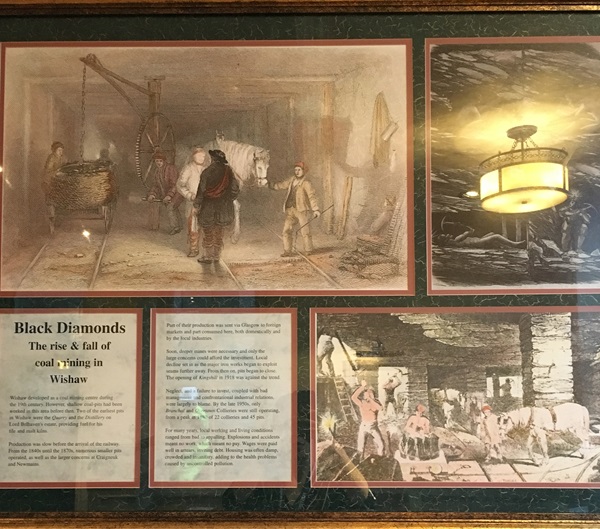

Illustrations and text about coal-mining in Wishaw.

The text reads: Wishaw developed as a coal-mining centre during the 19th century. However, shallow coal-pits had been worked in the area before then. Two of the earliest pits in Wishaw were the Quarry and the Distillery on Lord Belhaven’s estate, providing fuel for his tile and malt kilns.

Production was slow before the arrival of the railway. From the 1840s until the 1870s, numerous smaller pits operated, as well as the larger concerns at Craigneuk and Newmains.

Part of their production was sent via Glasgow to foreign markets and part consumed here, both domestically and by the local industries.

Soon, deeper mines were necessary and only the large concerns could afford the investment. Local decline set in as the mayor iron works began to exploit seams further away. From then on, pits began to close. The opening of Kingshill in 1918 was against the trend.

Neglect, and a failure to invest, coupled with bad management and confrontational industrial relations, were largely to blame. By the late 1950s, only Branchal and Overtown collieries were still operating, from a peak in 1880 of 22 collieries and 45 pits.

For many years, local working and living conditions ranged from bad to appalling. Explosions and accidents meant no work, which meant no pay. Wages were paid well in arrears, inviting debt. Housing was often damp, crowded and insanitary, adding to the health problems caused by uncontrolled pollution.

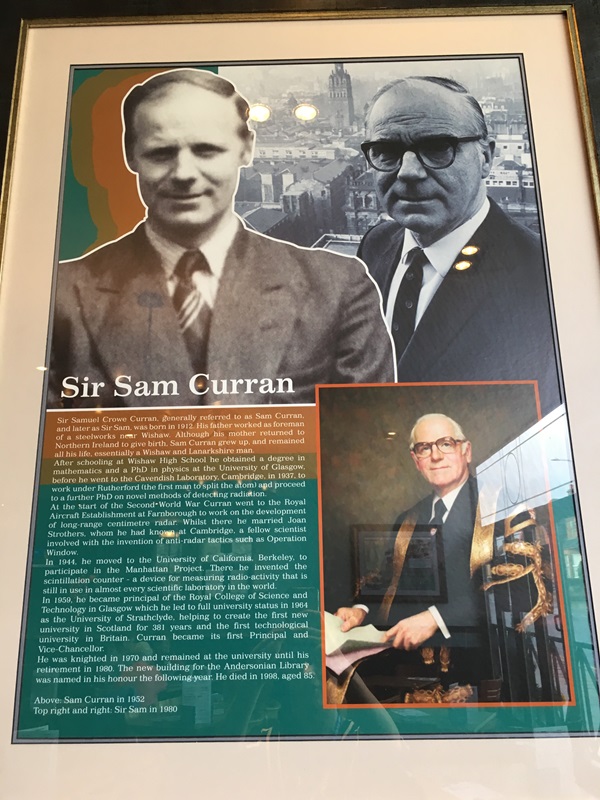

Photographs and text about Sir Sam Curran.

The text reads: Sir Samuel Crowe Curran, generally referred to as Sam Curran, and later as Sir Sam, was born in 1912. His father worked as foreman of a steelworks near Wishaw. Although his mother returned to Northern Ireland to give birth. Sam Curran grew up, and remained all his life, essentially a Wishaw and Lanarkshire man.

After schooling at Wishaw High School he obtained a degree in mathematics and a PhD in physics at the University of Glasgow, before he went to the Cavendish Laboratory, Cambridge, in 1937, to work under Rutherford (the first man to split the atom) and proceed to a further PhD on novel methods of detecting radiation.

At the start of the Second World War Curran went to the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough to work on the development of the long-range centimetre radar. Whilst there he married Joan Strothers, whom he had known at Cambridge, a fellow scientist involved with the invention of anti-radar tactics such as Operation Window.

In 1944, he moved to the University of California, Berkeley, to participate in the Manhattan Project. There he invented the scintillation counter – a device for measuring radio-activity that is still in use in almost every scientific laboratory in the world.

In 1959, he became principal of the Royal College of Science and Technology in Glasgow which he led to full university status in 1964 as the University of Strathclyde, helping to create the first new university in Scotland for 381 years and the first technological university in Britain. Curran became its first principal and vice-chancellor.

He was knighted in 1970 and remained at the university until his retirement in 1980. The new building for the Andersonian Library was named in his honour the following year. He died in 1998, aged 85.

Above: Sam Curran in 1952

Top right and right: Sir Sam in 1980.

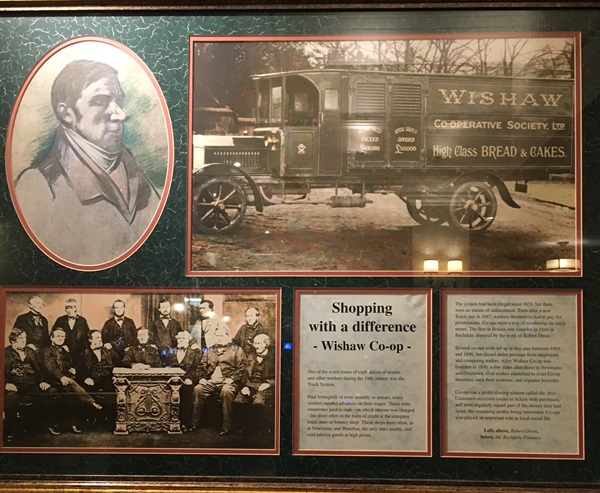

Prints, an illustration and text about Wishaw Co-op.

The text reads: One of the worst forms of exploitation of miners and other workers during the 19th century was the Truck System.

Paid fortnightly or even monthly in arrears, many workers needed advances on their wages. These were sometimes paid in cash – on which interest was charged – but more often in the form of credit at the company truck store or ‘tommy shop’. These shops were often, as at Newmains and Waterloo, the only ones nearby, and sold inferior goods at high prices.

The system had been illegal since 1831, but there were no means of enforcement. Even after a new Truck Act in 1887, workers themselves had to pay for prosecutions. Co-ops were a way of combating the truck stores. The first in Britain was founded in 1844 in Rochdale, inspired by the work of Robert Owen.

Several Co-ops were set up in this area between 1860 and 1890, but closed under pressure from employers and competing traders. After Wishaw Co-op was founded in 1890, a few years after those in Newmains and Overtown, rival traders combined to evict Co-op members, sack their relations, and organise boycotts.

Co-ops ran a profit sharing scheme called the ‘divi’. Customers received tokens or tickets with purchases, and were regularly repaid part of the money they had spent, the remaining profits being reinvested. Co-ops also played an important role in local social life.

Left: above, Robert Owen, below, the Rochdale Pioneers.

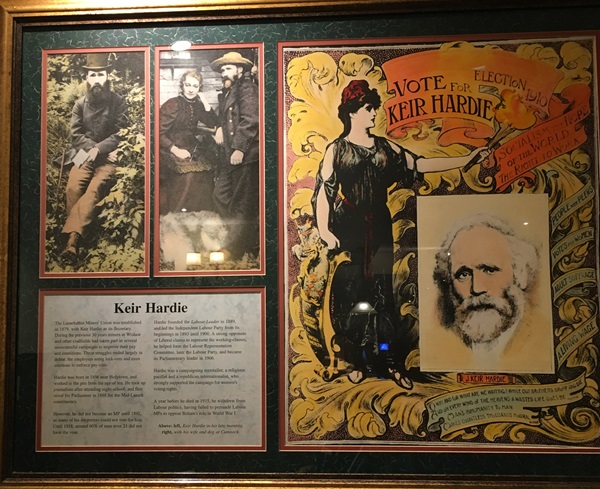

Prints and text about Keir Hardie.

The text reads: The Lanarkshire Miners’ Union was established in 1879, with Keir Hardie as its secretary. During the previous 30 years miners in Wishaw and other coalfields had taken part in several unsuccessful campaigns to improve their pay and conditions, these struggles ended largely in defeat, the employers using lock-outs and even evictions to enforce pay-cuts.

Hardie was born in 1856 near Holytown, and worked in the pits from the age of ten. He took up journalism after attending night school, and first stood for Parliament in 1888 for the Mid-Lanark constituency.

However, he did not become an MP until 1892, and many of his supporters could not vote for him. Until 1918, around 60% of men over 21 did not have the vote.

Hardie founded the Labour Leader in 1889, and led the Independent Labour Party from its beginnings in 1893 until 1900. A strong opponent of Liberal claims to represent the working classes, he helped form the Labour Representation Committee, later the Labour Party, and became its Parliamentary leader in 1906.

Hardie was a campaigning teetotaller, a religious pacifist and a republican internationalist, who strongly supported the campaign for women’s voting rights.

A year before he died in 1915, he withdrew from Labour politics, having failed to persuade Labour MPs to oppose Britain’s role in World War One.

Above: left, Keir Hardie in the late twenties, right, with his wife and dog at Cumnock.

An illustration of a bonder warehouse.

An illustration of worm tubs.

An illustration of a still house.

A photograph of Main Street, Wishaw, c1908.

A photograph of East Cross and Main Street, Wishaw, c1910.

A photograph of Wishaw, c1906.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk